Cue the complaints – I’m going to go off on a tear about “the kids today.”

Presently, there seem to be only two ways for young women to become stars in the pop music world, and it is rare when either is subverted. Path one: Start out as a Disney Channel teen queen, build your audience through a majority of songs that are innocent, and a few outliers that do more than flirt with double entendre. Announce your brand new “grown-up” album whereby the double meanings are no longer subtext but context, right up in your face, just like the half-naked record cover art rendered in “tasteful” grays. (See: Christina Aguilera “Genie in a Bottle” to “Dirrty” and onward, then see Demi Lovato, Selena Gomez, and Ariana Grande.)

Path two: Go right to sexy. Cut to the chase. Your songs are straight up club bangers and you have no time to mess with the slow climb. Up for anything, now. You don’t have many options moving forward. You keep pushing the sex angle or you go make a country album. However, your sex appeal is not your own and your “brand” is carefully constructed by teams of writer-producers who, essentially, design the outfit and then seek a body to fill it.

(A point worth noting: this is not a new practice by any stretch. Just look at Phil Spector and the many girl groups that arrived under his aegis, or Berry Gordy’s Motown, and you see the writer-producer model is regressive.)

It sounds cynical, but the music industry is still male-dominated and very cynical, and that often means that female performers feel obligated to play into age-old types. Complete dominance of the industry on one’s own terms is incredibly rare. Adele has been rightly celebrated for her achievements and lack of compromise, and few will fight to get to that same plateau.

It sounds cynical, but the music industry is still male-dominated and very cynical, and that often means that female performers feel obligated to play into age-old types. Complete dominance of the industry on one’s own terms is incredibly rare. Adele has been rightly celebrated for her achievements and lack of compromise, and few will fight to get to that same plateau.

Some won’t even try too hard, by their own admission. I listened to a BBC interview with a current pop star/songwriter who swears she has total control, but her considerable catalog of songs roughly have the same beat and synth instrumentation. She sings about partying, getting drunk on love and other stimulants, and makes it clear that she wants it now, whatever you choose “it” to be. She is not tied to a record label, but has adopted all the traits in order to make it. In the interview, she admits to not liking singing. She prefers the studio setting where she can flip on the autotune so she instantly sounds “amazing.” She touts complete autonomy but proves to have none through her description. She appears to model her career after Madonna, but she’s not even close.

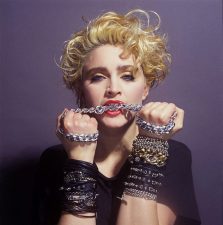

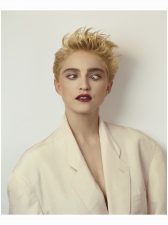

Madonna burst upon the music scene in 1983, and in this case, burst is appropriate. Seemingly overnight, middle- and high-school girls went from the fashion of whatever their parents bought them at the back to school sale to wristbands and fishnets. It confused us guys, believe me. We were previously coming to terms with the girls in our classes sporting shoulder pads and The Go-Gos attitude, and now, well this was something we couldn’t have expected. It happened so fast. She captured attention immediately, and just as quickly, it appeared she was in total control of her destiny.

Madonna burst upon the music scene in 1983, and in this case, burst is appropriate. Seemingly overnight, middle- and high-school girls went from the fashion of whatever their parents bought them at the back to school sale to wristbands and fishnets. It confused us guys, believe me. We were previously coming to terms with the girls in our classes sporting shoulder pads and The Go-Gos attitude, and now, well this was something we couldn’t have expected. It happened so fast. She captured attention immediately, and just as quickly, it appeared she was in total control of her destiny.

How so? Because Madonna courted controversy like a hunter, the kind of controversies that record executives hated their acts getting into because it meant lots and lots of explanations. Madonna tweaked icons (Marilyn Monroe in the “Material Girl” video, or the German Expressionist imagery of Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis” in the “Express Yourself” video), religion (“Like A Prayer”), and difficult subject matter. A song like “Papa Don’t Preach,” whereby the protagonist is asserting her authority to follow through with having a baby out of wedlock is worlds away from Diana Ross and the Supremes’ “Love Child” (1968) less than twenty years before. Seen through the eyes of the child as being a hard and sad life, “Love Child” was accepted as a cautionary tale. In a sense, the mother is punished as the child bears the sins of the parent, thus the puritanical balance is struck and audiences of the time could deal with it.

Yes, Madonna used sex as a tool in her career. It’s impossible to say otherwise, considering the troika of the 1991 movie Truth or Dare, 1992’s Erotica album, and it’s accompanying photo book Sex. Still, it hardly seemed like Sire Records head Seymour Stein was pushing her to be more explicit. If anything, he may have actively tried to tamp down those tendencies, subsequently causing Madonna to found her Maverick Entertainment company. (This is, of course, speculative and based only on the circumstantial.) As hackneyed a buzzword as it has become, it seems particularly true that Madonna was empowered.

What’s also true is that when she wanted to really grab your attention, she did so with little to no overt sexual involved, and this was also by design. She knew what you’d come to expect from her, so when she demanded your full engagement, she did it by wearing more, not less. She’d use that full-throated voice instead of the sometimes pinched, younger sounding affectation employed on those early hits. She could sing very well and, occasionally, that was enthralling enough.

Here are two examples that stand out. The first time people had to honestly reckon with Madonna as a mature entity was with “Live To Tell,” a song recorded for the film At Close Range. The movie starred Sean Penn, who would become Madonna’s first husband. The song would ultimately land on her True Blue (1986) album.

Built around music originally composed by Patrick Leonard for the movie Fire With Fire, Madonna wrote the lyrics and subsequently reworked the melodies with the producer. At Close Range is a moody drama about a Pennsylvania-based crime family directed by James Foley and seemed as far away from Madonna’s persona as one could get. (Foley also directed the music video for “Live To Tell.”) One could not easily put Leonard and Madonna together as natural collaborators and expect much. That was the point. In Leonard, she found someone that appreciated risks and embraced subversion. Their further efforts eventually yielded “Oh Father” from the Like a Prayer album from 1989.

Leonard was a big ideas kind of guy who would, in interviews, cite a host of progressive rock influences, eventually working as the producer on Roger Waters’ album Amused To Death. Leonard was also part of the duo Toy Matinee with Kevin Gilbert.

Both songs, “Live To Tell” and “Oh Father,” flirt with secrets. The former, in keeping with the narrative of the film it eventually accompanied, places the eyewitness narrator in jeopardy.

“A man can tell a thousand lies

I’ve learned my lesson well

Hope I live to tell

The secret I have learned, ’till then

It will burn inside of me”

This is about as far from the singer’s hedonistic tendencies as one could get.

The latter song digs a little deeper into Madonna’s…how to put this without being dismissive?…father issues. If you look at those first four studio albums, there is a reoccurring theme of resentment toward patriarchal authority, be it from the church and the dogma of Catholicism, of directly from a father.

Her mother died at age 30 of breast cancer in 1963. Madonna would have been around five years old at the time. It had once been assumed that the singer took the name “Madonna” because it further teased the reactionary positions she took, but it is, in fact, her real name, just as it was her mother’s.

She and her father bonded through their mutual grief, but Silvio Ciccone eventually remarried three years later. Madonna resented this, leading to behaviors that were viewed as punishment to him. These digs, great and subtle, are seen throughout her early work.

“Oh Father” has a lot to unpack.

It is, at one time, a shot across the bow of the Vatican, using the phrase so common to those who spent time in a confessional:

“Oh Father I have sinned”

But this is more an allusion than a direct statement, a call-out to the very strict ways a Catholic upbringing can entail. Things get more personal:

“It’s funny that way, you can get used

To the tears and the pain

What a child will believe

You never loved me”

“Seems like yesterday

I lay down next to your boots and I prayed

For your anger to end”

Her declaration in the chorus is rebellious in text, but musically haunted. It is no victory dance.

“You can’t hurt me now

I got away from you, I never thought I would

You can’t make me cry, you once had the power

I never felt so good about myself”

Rather than beating on that one note, however, the singer offers another side, a laurel of understanding:

“Oh Father you never wanted to live that way

You never wanted to hurt me

Why am I running away”

“Maybe someday

When I look back I’ll be able to say

You didn’t mean to be cruel

Somebody hurt you too”

In interviews, Madonna was quoted, “Like all young girls, I was in love with my father and I didn’t want to lose him. I lost my mother, but then I was my mother… and my father was mine… When he married my stepmother, it was, ‘OK, I don’t need anybody.’ I hated my father for a long, long time.”

The singer has not made statements citing physical abuse from her father, even though the song’s tenor would allege as much. It was the emotional abuse that drove a lot of Madonna’s rebellion, fueled by the births of her step-siblings which took the majority of attention away from her. Imagine this: for a brief period of time, father and daughter were a nation unto themselves, and then, that nation was filled with others. If, in fact, Madonna was emotionally moved to the side as she claims, it explains so much about what we know about her.

“Oh Father” is, musically, a gorgeous track – graceful and weighty at one time without feeling like pandering to the awards ceremonies – and a pinnacle of her creative output. Her first single, “Everybody,” debuted in October 1982. “Burning Up” followed in March 1983. Neither of these songs could possibly alert the audience to what she would be capable of roughly seven years later. Madonna is famous for her persona-bending but not as much for the material she produced throughout, and that is unfair. She was, by the late 1980s, firmly in control over what she did and how it came out to the public.

The music video was directed by David Fincher, the onetime employee of Industrial Light and Magic, later the famed director of Seven, Zodiac, The Social Network, and Gone Girl.

Contrary to the multiple paragraphs above, I am not a diehard Madonna fan. I don’t wince when her songs show up on the radio, but I don’t formally own any of her albums.

But here’s the thing that makes her special. She was always Madonna, even though she was constantly tweaking what that precisely was. She was and remains a singular, unique presence, whether you like her or not. She strove to maintain that individuality. The only other young performer from that era to match that aim was Cyndi Lauper.

Thus the old guy rant. Madonna had skin in the game (sometimes too much) and had all the risk. The reward was never guaranteed. Modern pop stars assume the position, make the noise albeit without a true sense of personal vision. Sia or Ryan Tedder or any number of producers send the track on down and the singer dutifully sings it. They do the voguing, crawl on the floor for the cameras, drink the champagne at the clubs for the paparazzi, they play the role. But so much of it feels unearned, and even a bit entitled. “I don’t have to break a sweat on this. If I just do what Madonna did, I’ll get what Madonna got.”

Thus the old guy rant. Madonna had skin in the game (sometimes too much) and had all the risk. The reward was never guaranteed. Modern pop stars assume the position, make the noise albeit without a true sense of personal vision. Sia or Ryan Tedder or any number of producers send the track on down and the singer dutifully sings it. They do the voguing, crawl on the floor for the cameras, drink the champagne at the clubs for the paparazzi, they play the role. But so much of it feels unearned, and even a bit entitled. “I don’t have to break a sweat on this. If I just do what Madonna did, I’ll get what Madonna got.”

Shamefully, they’re often right. People aren’t called out for phoning it in anymore. If anything, such has been integrated as part of the process, and even when the resulting song is a catchy earworm, there’s still something not quite right about it. Like or dislike Madonna, the majority of her career was the antithesis of “phoning it in.” She looks, to the world, like the Queen of Path Two, but most on that trajectory will never produce tracks that will thrive fifteen steps away from the hypersexualized persona.

Madonna accomplished that, actually, more than twice. It may well be time for a reassessment of her music, away from calls to dancefloor action, the calls to bedroom action, the belly shirts, no shirts, the lip-licks with Britney and Xtina…one is likely to find a surprising level of substance just underneath the layer of concealer.