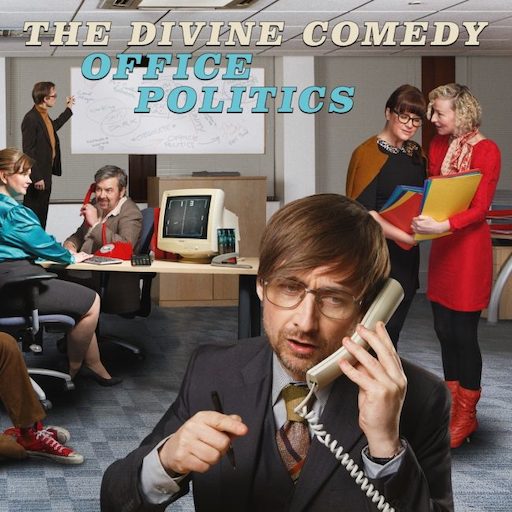

The latest album from The Divine Comedy, being largely singer/songwriter Neil Hannon, is a mixed turn on the pommel horse. Fortunately, the weight shifts more toward the positive than the negative, but it is impossible to avoid the times where the songs on Office Politics don’t stick the landing.

Provocatively, the record is a loose concept album about work, the mundane moderne, the effect it has on work/life balance and, ultimately, how technology may yet see us out the door as the tools become so good that the robots would prefer we weren’t left in the mix.

The record starts off strong with the rousing “Queuejumper,” with its taunting narrative and its male voice choir backing that pokes all those who feel the need to play “by the usual rules.” If you’ve ever been stuck at a red light as some arrogant jerk three spaces behind you gears up and blasts past, unobstructed by a single police-person, you might get a vicarious jolt from the lyrics.

Other standouts on the record include the sweet domestic slice-of-life of “Norman and Norma” which, by the end, takes a unique turn. After that is the spiky “Absolutely Obsolete” which neatly parallels a failed love relationship with the feeling one gets when they’re pushed out of a job. The analogy is subtle, but undeniable, and so is the pop-by-math-rock guitar line. It is reminiscent of Field Music, a group which I suspect draws inspiration from The Divine Comedy.

Hannon’s cleverness fuels the retro-tastic “You’ll Never Work In This Town Again.” Sounding like something from an early ’60s comedy, this track has quite a bit of swing to it, but also shows a bit of the difficulty of the album in full. Some background: the song’s title is the stereotypical line spouted in a movie about Hollywood mayhem when a studio head or a major player in industry kicks out the young know-it-all who is intent on shaking things up. The trick here is that Hannon really means technology, robots, and the inventions which are taking over the jobs that were once performed by people, literally meaning the “crazy algorithm” has absorbed all the tasks. Luckily, he doesn’t lay things on too thick, which might have dragged down the track entirely.

Other tracks don’t fare as well, and there are times where Hannon’s lyrical prowess is overtaken by weird “red pill” tonalities. He’s going to teach you about the world and reality in general, it seems, so if you don’t want to cloud your brain with ignorance, you better listen up. The album’s title track – which found me recalling The Nails’ “88 Lines About 44 Women” – is tedious. “Psychological Evaluation” beats the man-vs.-machine narrative again, with “The Synthesiser Service Centre Super Summer Sale” following after doing its best to stick you in the ribs with a unwelcoming “Get it? Get it?!” You get the punchlines in the first 30 seconds, but there’s still a minute-plus to go.

Here’s what gets me. This is a double album, and had it been seriously pared back, it would have been a stunning single album. I know this is a fallback position critics use when there are songs on an album that they like, tied up with tracks they don’t, but I can’t recall last when such a drastic juxtaposition was this obvious and, in my opinion, unnecessary.

Then again, if one used my own measuring stick against the record, we might lose “Phillip and Steve’s Furniture Removal Company,” a thematic figment of a sitcom creator’s mind wherein Phillip Glass and Steve Reich have said furniture removal company in New York City in the 1960s. “Hilarity ensues.” The sitcom theme, such as it is, uses the language(s) of minimalism to drive home the non-verbal joke. Thank goodness that Hannon knows and trusts his audience enough to not feel that such an esoteric gag needed to be mooted from the start, but I guarantee you that the critics who don’t have experience with tape loops, repetitive-cycle composition, and the like will direct their negativity toward this.

I couldn’t say Office Politics is peak Divine Comedy, but there’s more to like than not, and I suspect that polarity will reveal itself in individual inclinations. The ideal album in your mind will not look like the ideal one in mine, and maybe that alone justifies how it turned out. For myself, however, I will need to do a bit of track-jumping.