To say that David Bowie ever stopped being respected would be a grievous falsehood, but he certainly fell out of fashion, particularly in the 1990s.

Point of fact, most “legacy” artists did. Few were able to ingratiate themselves into the alternative rock graces as well (or as honestly) as Neil Young did with Pearl Jam. Bowie was close, however. Among his adherents was Nine Inch Nails founder Trent Reznor. Bowie cited the works of Godspeed You Black Emperor and Pixies as important and worth your attention.

Still, the collection of albums between 1993’s Black Tie White Noise and 1999’s Hours lingered in an odd nether-region. Ever ambitious, these recordings wear the auteurist-provocateur emblem that all of Bowie’s best recording have, but because of so much noise above in the atmosphere, these records didn’t have the same cache. They resided with a lot of long-timers who, in that era, were being drowned out by the cool kids.

Still, the collection of albums between 1993’s Black Tie White Noise and 1999’s Hours lingered in an odd nether-region. Ever ambitious, these recordings wear the auteurist-provocateur emblem that all of Bowie’s best recording have, but because of so much noise above in the atmosphere, these records didn’t have the same cache. They resided with a lot of long-timers who, in that era, were being drowned out by the cool kids.

In retrospect, they all seem of a piece, an integral part of Bowie’s constant evolution, but had there not been the reappraisal after Heathen (2002) right up to the near canonization via The Next Day (2013) and Blackstar (2016), where would albums like 1995’s Outside sit?

Outside is plenty dark. A concept album, it tells the story of an incredibly bleak future, an old-school gumshoe detective, an artist that is also a sociopath who creates her works from the organs of dead people, and in this sense, it was an appropriate album for the times. It fit in with the bleaker worldview of the so-called grunge movement while also flirting with the nihilism of the industrial music of the era. Through distortion and pitch-shifting, Bowie plays all the roles: Nathan Adler, the detective; Baby Grace Blue, the young teenage victim and, gruesomely, the work of art; Ramona A. Stone, artist/presumed murderess; Leon, a streetwise intermediary; and Algeria Touchshriek…well, maybe that name says enough.

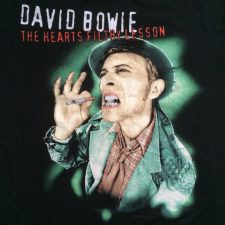

Bowie envisioned an ongoing narrative, which lends clarity to the record’s official title: 1. Outside. He imagined an audio novel, divided into three concept albums, and further exploration of this alternate end of the century, as described by a lyric from “I Have Not Been To Oxford Town” – “Toll the bell, pay the private eye, all is well, twentieth century dies.” That continuation wasn’t implausible either. The first single, “The Heart’s Filthy Lesson,” made some waves and was even included as the end credit score for the equally grotesque film Seven.

Bowie envisioned an ongoing narrative, which lends clarity to the record’s official title: 1. Outside. He imagined an audio novel, divided into three concept albums, and further exploration of this alternate end of the century, as described by a lyric from “I Have Not Been To Oxford Town” – “Toll the bell, pay the private eye, all is well, twentieth century dies.” That continuation wasn’t implausible either. The first single, “The Heart’s Filthy Lesson,” made some waves and was even included as the end credit score for the equally grotesque film Seven.

For all of the daring that was being put out by the record and the guy who made it, I recall the biggest news that the album made was through the reunion of Bowie with producer Brian Eno, representing one of the strangest reversals of fortune I could think of. Back in the years of the “Berlin Albums,” Eno – experiencing a level of success with his ambient recordings that seemed so different from his own glam rock roots with Roxy Music – was a part of the collective with Bowie as the most recognizable name of the lot. In intervening years, thanks to production work with Devo, Talking Heads, and crucially with U2 on the resoundingly successful The Joshua Tree, the tables turned somewhat. “Eno’s producing Bowie? What an extraordinary thing!”

The album did not lack for singles or potential singles. “Hallo Spaceboy” was the third such offering from the record. “I Have Not Been To Oxford Town” was a funky earworm that could have performed, was it not for its narrative specificity that might have tripped up such an option. “Thru’ These Architects Eyes” is a pop song with an unhinged quality. “We Prick You” likely was undone because the label, Virgin Records, assumed (rightly) that ’90s radio would have had difficulty broadcasting a song with “prick” in the name, even though it was used in its proper context.

The album did not lack for singles or potential singles. “Hallo Spaceboy” was the third such offering from the record. “I Have Not Been To Oxford Town” was a funky earworm that could have performed, was it not for its narrative specificity that might have tripped up such an option. “Thru’ These Architects Eyes” is a pop song with an unhinged quality. “We Prick You” likely was undone because the label, Virgin Records, assumed (rightly) that ’90s radio would have had difficulty broadcasting a song with “prick” in the name, even though it was used in its proper context.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BKtgykkbDA0

I do not know the details of this, but it is my assumption that the inclusion of “Strangers When We Meet” at the very end of the disc was a hedge-bet. Originally released as part of Bowie’s soundtrack to the BBC2 serial The Buddha of Suburbia (1993), it bears none of the narrative hallmarks of the Nathan Adler story. It sounds like a classic Bowie pop tune and, indeed, it is one of his best from this era. It nonetheless sticks out like a sore thumb as a tender, romantic tune after the grim and scab-speckled look into the alternate ’90s that Outside predicted.

The track is produced by David Richards, who was the producer for Queen’s later records. This association is worthy of note. Recall that one of Bowie’s most recognized tunes today is his collaboration on “Under Pressure,” from the album Hot Space (1982). You wouldn’t be faulted for thinking this was, back in the day, a massive hit for both artists, but it wasn’t. It too resided in that nether-region for many years until one Robert Van Winkle (aka Vanilla Ice) sampled it for his hit “Ice Ice Baby.” That led audiences to rediscover the original. David Richards was not the producer of Hot Space, but this helps illustrate the circuitous nature of Bowie’s work life.

The track is produced by David Richards, who was the producer for Queen’s later records. This association is worthy of note. Recall that one of Bowie’s most recognized tunes today is his collaboration on “Under Pressure,” from the album Hot Space (1982). You wouldn’t be faulted for thinking this was, back in the day, a massive hit for both artists, but it wasn’t. It too resided in that nether-region for many years until one Robert Van Winkle (aka Vanilla Ice) sampled it for his hit “Ice Ice Baby.” That led audiences to rediscover the original. David Richards was not the producer of Hot Space, but this helps illustrate the circuitous nature of Bowie’s work life.

Further, with Eno returning as Outside‘s producer, you see a complicated blend of personalities from across Bowie’s career. Pianist Mike Garson and Carlos Alomar represent one phase, Tin Machine bandmate Reeves Gabrels represents another, and Sterling Campbell points to the future. Clearly, once you reached Bowie’s inner circle and should you drift out, you would not be away from it permanently.

Where does Outside reside in the greater scheme of things? Bowie himself reckoned this post-apocalyptic vision was in tune with Diamond Dogs (1974), and the depictions of dehumanization – either for art’s sake or for political gain – toll that bell for modernity, practically everytime we read the news. The species has begun to reject its status as objects – as sex creatures only present for the pleasure of half the population; as obstacles that block power and should, therefore, be destroyed and removed like some clot – and is beginning to once again assert its right to be individual, to have meaning, value, and respect in the singular, versus the faceless and nameless mass. Outside depicts a conclusion, where the literal guts of the dispossessed, abused, forgotten, and disregarded, could be hung on a gallery wall to bring honor (and lots of money) to the vivisectionist who did the deed “in the name of art.” It is a gory extrapolation of attitudes, both then but especially now.

Where does Outside reside in the greater scheme of things? Bowie himself reckoned this post-apocalyptic vision was in tune with Diamond Dogs (1974), and the depictions of dehumanization – either for art’s sake or for political gain – toll that bell for modernity, practically everytime we read the news. The species has begun to reject its status as objects – as sex creatures only present for the pleasure of half the population; as obstacles that block power and should, therefore, be destroyed and removed like some clot – and is beginning to once again assert its right to be individual, to have meaning, value, and respect in the singular, versus the faceless and nameless mass. Outside depicts a conclusion, where the literal guts of the dispossessed, abused, forgotten, and disregarded, could be hung on a gallery wall to bring honor (and lots of money) to the vivisectionist who did the deed “in the name of art.” It is a gory extrapolation of attitudes, both then but especially now.

With that, it’s not a vision people want to cling to. They’d prefer the more carefree joys of “Let’s Dance,” or the generation revolution of “Changes,” or the de facto anthem that “Heroes” has become. It seems that whenever someone now says, “I want to sing a song to lift up my musical icon, David Bowie,” they sing “Heroes.” Sure, it’s an honor, but if Bowie was still alive, I’d have to think he’d rankle at the unoriginality of the effort. “I did hundreds of songs,” I imagine him saying, “yet you all want to just sing the same one?”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M8YAzDDOCbY

No, there isn’t much to feel good about with Outside, and that pessimism lingered into the equally audacious follow-up Earthling (1997) which dipped a toe into heavy drum-and-bass and scared up “Little Wonder” and “I’m Afraid of Americans.” The story of Nathan Adler ended at one. Perhaps it is for the best. The work that followed was just as worthwhile, and one could hardly fathom how much lower, and how much darker, Bowie’s futurevision could get.

Outside is an ugly record that appeared in a time where ugly records were showing up with great frequency, but where the other ’90s albums tended to show the bad world where it was, Outside dared to show where it was going, and still had songs with deep hooks and hummability. Someone may have told Bowie that such a dour exploration would be like career suicide, to which he responded with the equivalent of his guts hanging on the wall, goading you to stare at it, reckon with it, or pointedly put a price on it.