It’s been a few months now since the Peter Jackson documentary The Beatles: Get Back debuted on Disney+. It arrived to much acclaim, maybe too much but we’ll tackle that in a moment. What is most important is to challenge this lingering notion that this miniseries”set the record straight” on the trove of film and audio assets accrued during the creation of what became the Let It Be film project.

Famously, Let It Be showed what seemed to be a highly dysfunctional unit on the brink of dissolution, as illustrated by George Harrison exasperatedly telling Paul McCartney “I’ll do whatever you want me to,” after what seemed to be endless nitpicking about Harrison’s guitar performance. Harrison would, at least temporarily, quit the band during these sessions.

The tricky part is this idea that The Beatles: Get Back corrects this perception. It does not. On the contrary, I think it bends the record as much as it always has been, but instead to the direction the fans wanted it bent, and in turn, said fans deemed it “truth.”

The truth is that there is no truth in film, not even in the most stringent documentary. Trust me, it doesn’t make me feel good to say this, because I genuinely like The Beatles: Get Back. Draw up a Venn diagram where The Beatles overlap music documentaries and you’ll find me square at center, but every documentary I’ve ever viewed was made by someone, often by several someones, and that requires a vision be it directorially, editorially, or cinematically. Like the subatomic structure that changes simply because you observe it, recording an event strips out objectivity. It has to, because the camera becomes the eye of the singular entity of the person saying where to shoot.

Maybe we should dig in.

The Content Problem

Upon it release, critics hailed The Beatles: Get Back as a monumental achievement, which it indeed was. Director Peter Jackson, best known for the epic Lord of the Rings trilogy, was given access to massive amounts of material captured during sessions that comprised what became the Let It Be film. Large portions of that film were shot in Twickenham Studios as the members of the band sought to develop music for their first major performance in many years. The sessions were strained by relationship issues, but also by the limitations of a movie studio set. Large, imposing, and hollow-sounding acoustically, McCartney, John Lennon, Harrison, and Ringo Starr felt out of their element and weren’t afraid of showing that. Add to that Let It Be director Michael Lindsay-Hogg was being too hands-on, getting in the way as the constituents attempted to get down to business.

The mood improved when the band left Twickenham and adjourned to a normal studio setting. It is here where the majority of The Beatles: Get Back is recorded, and yes, interactions improved greatly. But most people didn’t see or hear this side. Instead, Lindsay-Hogg’s final product seemed dark and dour. It was everyone’s worst family get-together writ large. This was the task for Jackson, a self-avowed Beatles fan, to get as much out before the public, seeing much of what occurred prior to the infamous Rooftop Concert.

There is among Beatles fans a strange obsession with whether the bandmembers stayed friends over the years. In some respects, this has become more important than the music itself, and so the prospect of a documentary that chased the gloom away from the final days of Beatledom instilled a degree of self-fulfilling prophecy to the project. This would be for them a way of chasing the lingering fear that, specifically, McCartney and Lennon were less than bros at the end of Lennon’s life, tragically taken by a bullet in New York.

Let’s not kid ourselves – The Beatles: Get Back is not a milestone. It is not a cinematic high water mark or act of the highest human achievement. It is a very, very good project, but first and foremost, it is content. There is a reason why Disney+ scheduled it’s premiere in that golden spot between Thanksgiving and Christmas, and why high profile Marvel and Star Wars properties were shooed away from that spot. It was to get subscribers to the streaming service, not to make a statement on the band, the music, or the controversies surrounding them.

We see, just a few months later, exactly this. You may have asked yourself this when seeing this late publication, wondering if I was going after old news. The Beatles: Get Back is now relegated to the dust of Tiger King and a million Carole Baskin memes, The Queen’s Gambit, Squid Game, and other pop culture fireworks that flashed brightly, twinkled out, and were no more.

It makes you wonder why the critics were so ecstatic over this project, heaping praise upon it with superlatives that ranged from strongly impressed to cultishly focused, stating this would change everything. In hindsight, not much. John Lennon would yet release his solo rebuke of Paul McCartney’s silly love songs, “How Do You Sleep?” McCartney would defend himself with the retort, “Some people want to fill the world with silly love songs, so what’s wrong with that?” Yoko Ono would be dragged down as a prime mover of the band’s breakup and that misperception, fueled by not-too-subtle racist language, carries on to this day. All this occurred after the events of The Beatles: Get Back. Just so that we are all on the same page: the band was still going to break up. It’s just that the softer, more polite version of it all in this rendition plays to critical bias (they were all friends), not against it (being the Let It Be we remember).

Safe to say that people got swept up in that moment in November/December 2021, and maybe their effusive praise got the better of their judgment.

The important question is whether The Beatles: Get Back is nearly as honest as we’d like to think it is.

Lev Kuleshov

Two things about Let It Be is that focus on the Twickenham anxieties, and the limitations of the filmmaking process: noisy conversations, dated-looking film. I think Peter Jackson did a marvelous job with both the film restoration and the audio, stripping out conversations that were once unintelligible. At the same time, the very-clean imagery affects your impressions of what’s going on. The grainy garishness of Let It Be was bound to color one’s impression of the depicted events. What once may have sounded like bickering with one voice going at and over another now has separation in the recent iteration – aided by impressive digital de-mixing – that could imply an artificial politeness. There’s more than a hint of the Lev Kuleshov effect happening here, I think.

According to Wikipedia, Kuleshov was “a Russian and Soviet filmmaker and film theorist, one of the founders of the world’s first film school, the Moscow Film School. He was given the title People’s Artist of the RSFSR in 1969. He was intimately involved in development of the style of film making known as Soviet montage, especially its psychological underpinning, including the use of editing and the cut to emotionally influence the audience, a principle known as the Kuleshov effect.

“Kuleshov edited a short film in which a shot of the expressionless face of Tsarist matinee idol Ivan Mosjoukine was alternated with various other shots (a bowl of soup, a girl in a coffin, a woman on a divan). The film was shown to an audience who believed that the expression on Mosjoukine’s face was different each time he appeared, depending on whether he was ‘looking at’ the bowl of soup, the girl in the coffin, or the woman on the divan, showing an expression of hunger, grief, or desire, respectively. The footage of Mosjoukine was actually the same shot each time.

“Kuleshov used the experiment to indicate the usefulness and effectiveness of film editing. The implication is that viewers brought their own emotional reactions to this sequence of images, and then moreover attributed those reactions to the actor, investing his impassive face with their own feelings.”

More shots of George Harrison smiling, intercuts of Linda McCartney and Yoko Ono vibing with the band, family interruptions with levity, not distractions, bright colors, no film grain, all these become editorial choices, editorial vision. You’re telling a story, but is it THE story or your interpretation of it? This is the pitfall of the documentary form.

I’m NOT saying that The Beatles: Get Back is being willfully deceptive. I don’t believe the band hated each other’s guts as Let It Be might have had us believe, and the unseen footage does wonders for pulling the narrative back from that brink. I’m just saying that the viewer could be just as easily swayed to the opposite, and Jackson as a fan might be subconsciously nudging things friendlier, too.

All storytelling is fiction, even the “factual” stuff.

What Should The Beatles: Get Back‘s Place In History Be?

We can’t forget this. The Beatles broke up. That is merely a fact that revisionism can’t bend back.

There are now two documentaries that present opposing profiles. One is going to appeal to a subset of the fandom that imagines a rosier outcome than what the rest take away from the other. If anything, these remind us that it is ultimately up to the viewer to decide, and taking either film (or any film) as gospel is a mistake.

How do I personally feel about The Beatles: Get Back? I think it is a remarkable process document, sometimes marred by bickering, sometimes revealing a future that might have been but was denied. As a George Harrison fan, I witness again and again these remarkable songs in gestation, ready to arrive under the Beatles banner, but denied because, in Lennon’s sniffy estimation, they’re only “Harrisongs.”

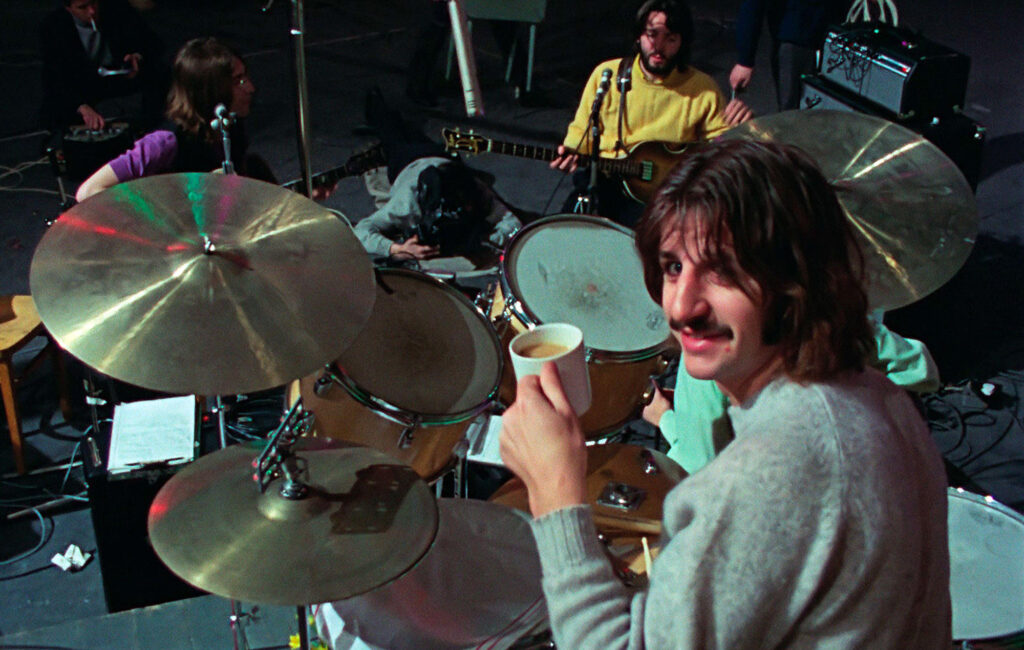

I watch as Ringo hangs back, not so much with the attitude of “not my circus, not my monkeys,” but with a wisdom of a few more years that the rest. He sees the push back Harrison is getting and probably presumes his input against the monolithic Lennon-McCartney bulldozer won’t add up to much. We’ve all been in those shoes.

Mostly, I watch how songs are written. They sometimes appear as magical as pixie dust, born from nothing. Mostly, they’re about showing up for work and digging down. There is regularly no romance about it, only that the core members made that effort.

I am now 52. My life has been surrounded by the Beatles legacy, but primarily connected to the post-Beatles output. McCartney’s Flowers In The Dirt and Harrison’s Cloud Nine are more relevant to me because I was there when they arrived, whereas The Beatles were here before I arrived. Each year, I see their influence in music, pop-culture, and media in general grow less and less. They will be soon enough like Duke Ellington, Irving Berlin, and even Elvis Presley; names we know as important, but whose actual impact is no longer felt. We realize that as digital music enters a continual cycle of tropes and cliches, that which came before it is bound to feel less like art and more like artifact.

Like I said at the start, I like The Beatles: Get Back. I think Peter Jackson has done a great service to fans, even as I state outright that I believe technology has enabled fan-service over veracity. It’s just that we must be honest with ourselves first and foremost. Do we like this film because it “tells the truth” or because it tells the truth we like, which really isn’t the truth?