Look, in an infinite universe where all iterations of events are possible – even probable – RTZ was never going to make it in any of them. But to explain why, we must take a road trip to Boston.

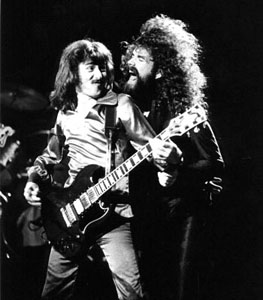

Boston, the wildly successful rock band from the 1970s, was not really a band at all, according to its leader Tom Scholz. In his account, the first album – featuring the rock radio staples “More Than A Feeling” and “Long Time” – are, in fact, proto bedroom pop conceived of and recorded by a self-professed tech geek. Scholz states the multi-layered guitars on the eponymous record, along with bass, keys and nearly everything else were performed by him on a homemade multitrack reel-to-reel recorder.

This statement, while considered the official testimony, is disputed. While not involved with the project, producer Tom Werman has said in interviews that he knew credited producer John Boylan very well, as they both frequented the halls and contract sheets of Epic Records in those days. In Werman’s estimation, Boylan would never simply slap his name on someone else’s work, especially if that work was a debut. If the recording were deemed to be flawed, that kind of cavalier attitude would reflect poorly on Boylan’s reputation so, no, he surely had something to do with the production of that record, asserted Werman in the past.

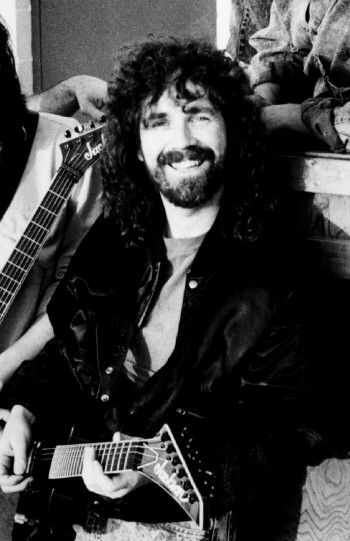

And to be fair, Werman has the circumstantial at his back, if not to prove his point, then to lend a tiny glimmer of verisimilitude to the complicated miasma that was Boston. On paper (and on stage) the band had four members: Scholz, singer Brad Delp, guitarist Barry Goudreau, and drummer Jim Masdea, all four of which were members of the band Mother’s Milk. Scholz worked for the photochemical company Polaroid, and his technical skills came in handy when it was time to build his home studio.

Jim Masdea was replaced by Sib Hashian, who according to the dominant record did the drums for both the 1976 debut and 1978’s Don’t Look Back. Masdea would return to the band in 1986 for the third record Third Stage, but even this is in question as the drums on the recording are clearly synth drums, so while it could be Masdea striking the pads, it could also be programming.

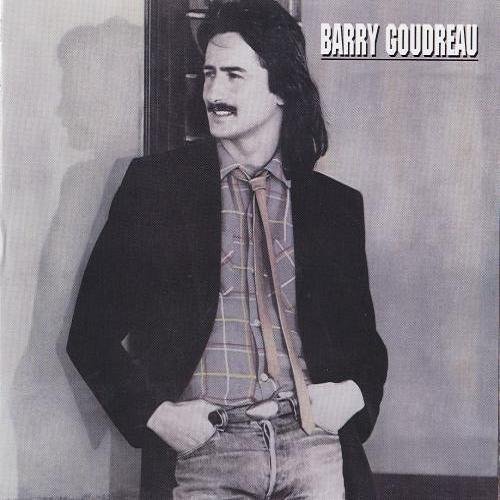

In 1980, with Boston in his rear-view mirror, Goudreau released his self-titled solo album featuring Delp on vocals as well as Fran Cosmo. It is all kinds of weirdly incestuous. By 1984, Goudreau formed the band Orion the Hunter, featuring Cosmo and former Heart member Michael DeRosier. Delp helped with the writing and background vocals, and considering five years had elapsed since Boston’s last album, it would have been safe to assume the former band was dead and done until, of course, it wasn’t (see the previous paragraph). In ’86, Delp was back on Third Stage. Another eight years after that, 1994’s Walk On would be the first Boston album without Delp as primary vocalist. That honor would go to…Fran Cosmo. Like I said: kind of incestuous.

But who could blame any of them for jumping on opportunities as they emerged? Even amid this chaotic dysfunction, this was a unit prone to falling away and coming back together, like clusters of magnets thrown hard at the ground. They would shatter, but they would reunite all over again, for better or worse.

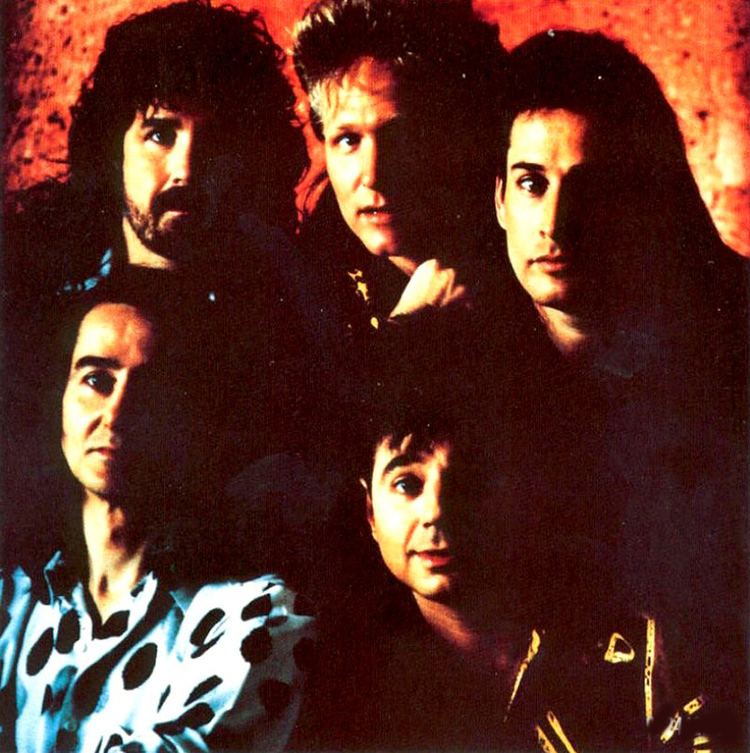

In the early 1990s, Barry Goudreau would form yet another new band, enlisting his longtime collaborator Delp, along with keyboardist Brian Maes, bassist Tim Archibald, and drummer David Stefanelli. They called the band RTZ, or “return to zero,” starting out once more from scratch, as it were. They were signed to Giant Records, a label founded by famed music agent Irving Azoff. The band provided a sound that, while not as thickly layered as Boston’s, certainly showed its cards in terms of overall album-oriented-rock presentation.

None of it really made a damn bit of difference. The fault for RTZ’s failure was not necessarily in Tom Scholz’s iron hard around the Boston legacy or infrequent recordings, or who did or did not do what, or the many, many legal actions for royalties for who did or did not do what. At long last, what wound up being RTZ’s true Achilles’ heel was that they were a straight-up rock and roll band.

Arriving in 1991, the debut Return To Zero was irrelevant on arrival. It sounded more like the storied arena rock of a latter-years Journey or Heart. But so what? These, along with the pop fluff of the era, hair metal swagger dudes, all of them got swept to the margins in the wake of the so-called Grunge Revolution of the ‘90s. Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, and so many others suddenly made bands like RTZ sound quaint, old, your dad’s favorite new band.

That is an incredible shame because, while the album does sound like a recording more at home in 1981 than 1991, that’s not a bad thing. In a sea of anger and angst, RTZ sang about love, light, hope, growing up and facing down your past transgressions, without being sickly sweet. The band could work a more negative line as well, but that wasn’t the raison d’etre for this group, and in a musical era where “everything sucks” was hardly ever followed up with, “but we can change it,” RTZ came off as an anomaly.

Goudreau’s guitar lines are everything you would hope from the presumptive guitar player from Boston. Listen to the solo in “This Is My Life.” Listen to the celebratory sounds of “Rain Down On Me” and “Every Door Is Open.” Listen to Delp’s voice because, no matter how long the debate goes on about who did what for Boston behind the six-strings, the truth is that it was his vocals that elevated that brand name to stratospheric heights, not the guitar-shaped spaceships on the album covers.

That merely glances the biggest problem here. You probably could fall in love with the band if you got to hear them, but that was not going to happen on rock radio. It did not help that the marketing of the band was so…predictable. The tracks chosen for the release campaign – “Face The Music,” “All You’ve Got,” and “Until Your Love Comes Back Around” – typify what a label head would tell a band are the singles, but this was occurring in the wake of anti-singles marketing.

I insist that, had Giant Records pushed “Rain Down On Me,” “Every Door Is Open,” the weightier “This Is My Life,” or the playful, honky-tonk inflected “Devil To Pay” instead, things might have been different. Not exorbitantly different, but not swimming through the footnote territories RTZ reside in.

Having just stated the rock world’s infatuation with the dour would make success difficult, it would not have been impossible. Released the same year, Mr. Big’s breakout hit, the ballad “To Be With You,” is a natural colleague to the sound of RTZ. If anything, RTZ would have sounded more mature and confident by comparison, and that is not a knock against Mr. Big. The track was a self-admitted afterthought for the band, as singer Eric Martin wrote the simplistic-but-charming song many years before, in his teens, and its inclusion on the Lean Into It album was last-minute, to say the least.

Fate is a joker. Of course, that would wind up the biggest hit of Mr. Big’s existence, challenged only minimally by their cover of Cat Stevens’ “Wild World.”

Return To Zero became one more in a long line of ‘90s releases where established performers were left ignored by the zeitgeist but, mercifully, the band did not follow it up with a second attempt, grungier, edgier, and altogether missing the mark. At least, I thought they did not. While writing this appreciation piece, I learned there was indeed a follow-up record. (Some apologist I am.) The recording, titled Lost, was released in 1998 by MTM Music and Avalon Japan. It was reissued in 2000 with a bonus track, and again in 2005 under the title Lost in America, and I knew nothing of any of it. I will seek it out and report accordingly, but I secretly dread finding out it was the band’s angsty over-correction for daring to be light of spirit in 1991.

Speaking of not being light of spirit, Boston returned in 2002 with the tellingly titled Corporate America. Brad Delp returned, but as a co-vocalist with Fran Cosmo. The record did okay despite its circumstances. Its chances were ultimately stymied by Tom Scholz suing the label it appeared on, Artemis Records.

While this would be the definitive end of the RTZ dream, controversy would continue both on musical and personal fronts. In 2007, Delp committed suicide. Frustratingly, Scholz would still include Delp after his death on the 2013 Boston album Life, Love & Hope. Some would view it as a tribute, that Scholz used vocals from demos and alternate takes to revive the classic Boston sound one last time. Others viewed it as cold and opportunistic, since there was clearly a lot of bad blood between the two men. Getting a couple more tunes from Delp, if from beyond the grave, seemed a tasteless act, but actually, not unexpected in the light of all the other things that happened.

The details surrounding Delp’s death would fill up an article all its own. However, I do not know if I am qualified to tell that story. In messaging found afterward, Delp spoke of living most of his life with the persistent notion of killing himself. You can find more details about this on the Internet, and about all I can add to this would be to say it is sad, tragic, and none of us are 100% good or 100% bad. We are complicated messes. By and large, the people who knew Delp personally felt he was more the former, frequently citing him as “the nicest man in rock and roll,” and we all should strive for that better ratio.

Taking all this into account, one must conclude that RTZ’s debut pretty much had the deck stacked against it. A story where the group succeeded and thrived afterward seems impossible to imagine. It’s the kind of thing hacky screenwriters dream up to wedge in a happy ending despite all plot threads leading to an opposing outcome.

But they tried very hard. Like the title of their second single proclaimed, they would give it all they’ve got, but it wasn’t enough.

The “Return to Zero” album was fairly successful as it produced three charting singles, including one in the Top 40.