Porcupine Tree started out as an elaborate deception in 1987 — and ended in 2018 with a pronouncement by the band’s founder, Steven Wilson, that “it’s finished.” However, when Porcupine Tree started releasing music mostly on cassette, Wilson and others concocted a whole backstory about how the band was really a 1970s-era progressive rock group like Pink Floyd. However, as the “joke” became a serious music effort, it became apparent to the band that it was time to ditch the hijinks of youth and own up to the fact that none of their fans really understood the joke that was being played on them.

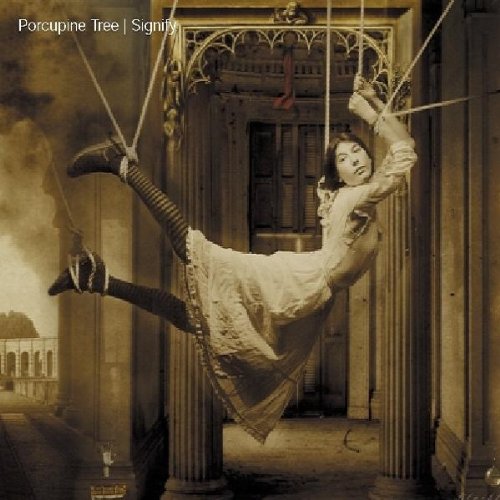

It was around 1996 when Wilson decided it was time to create a recording by Porcupine Tree — the real band. While Signify is not their strongest recording, it does contain many themes Wilson used in subsequent recordings to address alienation, religion, and a kind of postmodern fracturing in modern societies. His use of taped samples on the album is often deployed in a deft way. Many of the samples work well within the context of the songs, and certainly reflect the way in which Wilson came of age musically. From Pink Floyd to hip-hop, it’s abundantly clear his Gen X sensibilities are on full display on Signify.

Pink Floyd is probably the closest comparison to Porcupine Tree’s music, but even that’s a bit of a stretch. Yes, both bands craft songs that are melodic, have more than a touch of psychedelia, and center on alienation. However, Porcupine Tree’s music sometimes crosses over into metal territory. What I love about what Wilson, Richard Barbieri, Colin Edwin, and Chris Maitland craft on this record is a kind of journey into the early effect the internet had on the mind of an individual. While the recording process was gradual and irregular, the members of the band were, according to Wilson, never in the same room together. So yes, while they didn’t play as a band by recording off the floor, each member’s contribution to the album — while based on Wilson’s demos — brought different tones, styles, and character to the songs. So, as a track-by-track RE: Visit of Signify gets underway, keep in mind that while Wilson is certainly the visionary of the group — often controlling the entire recording process — to me, it’s the band who improved these songs from demo form into a unique sonic experience.

The soundscape that starts the album, “Bornlivedie,” is an effective intro into a hard-rocking, but grooving title track that seems like it should have lyrics, but clearly doesn’t. It’s not apparent that “Signify” is any kind of album overture, but it does start the record in a way that really grabs a listener’s attention.

“Sleep of No Dreaming” begins with more than an allusion to suicidal thoughts: At the age of sixteen/I grew out of hope/I regarded the cosmos through a circle of rope. However, the narrator then decides to throw out his plan, onto his wheels and “emptied” his head of his “childish ideals.” From there, things get kind of surreal with a kind of spilling over of what’s on television into reality. The lyrics are kind of cryptic and vague but when fit into the context of the song with the soaring chorus, spacious guitar work, and tense verses, it becomes one of a handful of radio-friendly songs on the album.

“Pagan’s” dream-like intro to “Waiting phase one” settles into a nice melodic form with a strong chorus, a solid groove bass line supplied by Colin Edwin, and a continuation of a journey of sorts wherein the narrator’s sense of dislocation is slapped out of a kind of stupor either through drugs or the feeling of nails across his skin. “Waiting phase two” is another dream-like instrumental that’s kept rooted by Edwin’s bass groove throughout the first part of the song. Then Chris Maitland shifts gears and takes the lead with some tasty drum patterns that play off of Wilson’s ethereal guitar work.

“Sever” continues the loose concept of the fracturing self with lyrics that are also splintered — well, all the lyrics are written in such a way that they appear disjointed and frayed. Clearly, that’s by design, but what is it that Wilson is trying to say? Well, one could view this as the way in which individuals can feel psychologically shattered by the technology that seems to know you more than you know yourself. The “ESP city” predicts what kind of tomorrow one will have by understanding what motivates a person on a daily basis. The “Oprah saviour” is certainly a charismatic personality who promises a better existence if only one follows her advice. There’s a desire to be free with the refrain of “Sever tomorrow” but it remains just that: a desire. As the battle rages, we hear the clashing of swords, and a foe saying, “That’s the only way to survive is on your knees” while laughing in a way villains often do in the movies.

“Idiot Prayer” starts off kind of peaceful, but the tension and the tempo starts to build as the instrumental takes off in a seven-minute tour de force with sampled voices that reminiscent of David Byrne and Brian Eno’s My Life in the Bush of Ghosts — but not in such a heavy-handed way. Wilson’s use of the taped samples is more spare throughout the song, which allows for more musically expansive moments until the groove starts driving with Wilson’s lead guitar work alternating between more rhythmic sections and outright shredding.

“Every Home is Wired” brings the record back to a more melodic feel, but those comforting tones strummed on a guitar give way to lyrics that reveal the cultural impact of internet culture on individuals and society at large. Remember, this album came out in 1996 when the internet was in a kind of infancy. The always-on connectivity made possible with portable computers (branded as “phones”) as appendages wasn’t even a thing. But does it matter? It seems when Wilson sings about the “neural rust” swimming through circuits to the wired home where the “Data in my head” creates conditions where “Part of me is dead” is as relatable today as it was in ‘96. What is that part? Well, if we flash-forward from 1996 to now, it can mean many things, but the loss of seeing each other as fully human and having genuine connections and conversations rusts our neural pathways. Instead — because every home is wired — engagement is far more important understanding. Kate Bush explored a similar theme of how being wired to technology replaces human connections in 1989’s “Deeper Understanding” from The Sensual World. Wilson is continuing that critique on Signify in a far more ethereal way.

“Intermediate Jesus” takes on the way in which charismatic religious individuals use the power of the pulpit (and technology) to spread a message of fear and salvation — which Wilson sees as another form of control. If the internet creates “neural rust” the preacher sampled in “Intermediate Jesus” is another off-shoot in the primacy of emotional engagement over genuine connections. Wilson hammers this point home when he mashes up a number of bumper sticker/headline phrases from the preacher to show how these trigger emotional responses that can engender tribalism and rabid moralism.

“Light Mass Prayers” has similarities to the intro of “Invisible Sun” by The Police, and acts as atmospheric interlude to the final track on Signify, “Dark Matter.” Oh, and what a lyrically dark song it is! Musically, it starts out quite hushed, then Chris Maitland’s 4/4 beat kicks in as the song starts to build. The allusion to suicide like in “Sleep of No Dreaming” is the first thing we hear: Inside the vehicle the cold is extreme/Smoke in my throat kicks me out of my dream. Things don’t get much better after that:

I try to relax but its warmer outside

I fail to connect, it’s a tragic divide

This has become a full time career

To die young would take only 21 years

Gun down a school or blow up a car

The media circus will make you a star

Dark matter flowing out onto a tape

Is only as loud as the silence it breaks

Most things decay in a matter of days

The product is sold the memory fades

Crushed like a rose

In the river flow

I am I know

The dream and failing to “connect” finds the narrator defeated in what he or she was trying to accomplish. Perhaps that desire for deeper human connections was “crushed like a rose” when technology killed off those links and replaced them with “dark matter” where engaging in (and gazing at) horrific violence leads to it being glorified in the “media circus” — like the surrealist violence depicted in Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers.

Or maybe the whole journey on Signify are the last moments before the narrator gets electroshock therapy to, as the tape sample at the end says, wipe away all those childhood traumas.

Whatever the case, Porcupine Tree’s first proper album makes for a musical experience that is largely melodic and atmospheric. However, like a David Lynch film, underneath what could be called The Familiar, are doors and windows that lead the listener into rooms that are haunting, tragic, and often entail an erosion of our collective humanity as technology establishes itself as the new order.