Insofar as one can have sympathy for a multimillionaire rock legend, a pang is elicited when the details of Robert Plant’s solo career get discussed. It seems people started nagging him for the details of the Led Zeppelin reunion the very moment the band’s odds n’ ends record, it’s last, Coda, landed on shelves.

That very nag is resurrected every following year, and with every solo record Plant puts out, as if his insistence that he has little desire to look back (and little need for the easy cash grab) never got said. It is a tiresome occurrence to those outside of the loop. Can you imagine the annoyance at the heart of it?

Oh, Plant is not entirely blameless. The first few solo records were not giving up the Zeppelin groove too easily to make reunions unthinkable. Pictures at Eleven (1982) featured the track “Slow Dancer” with Cozy Powell thumping the skins, it’s exotic tones hinting at “Kashmir” just a teeny bit. This is one of several songs that hinted Plant was keeping one foot in that door, at least in the minds of the speculators. Much of the noise, however, was muted when Shaken ‘n Stirred landed in 1985. It was slicker, glossier, and reflected the then-present in a way the previous discs hadn’t. Plant, on his Digging Deep podcast, gave some props to David Byrne for inspiration. “Sixes and Sevens” has a Synchronicity-era Police sheen. The major single from the disc, “Little by Little,” had some sonic threads to fourth-quarter Zeppelin, but not clearly. You had to dig a bit to make a case that this was still a nod to Plant’s past.

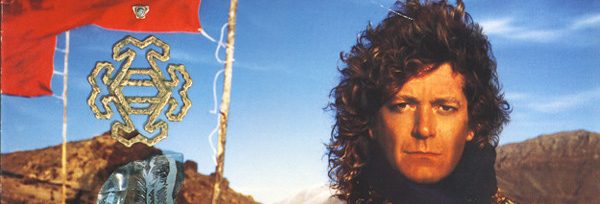

In 1988, enough was enough and Plant dropped an album that was so modern, so un-Zep-like, it temporarily hushed the chattering classes. And it tweaked them at the same time (but we’ll get to that momentarily). The first single of 1988’s Now and Zen, “Tall Cool One,” might as well have been The Cars. At times, Plant’s delivery even sounds a little like Ric Ocasek. It was a driving, pulsing, indelibly 1988 kind of song, complete with bits and snips of storied Zeppelin tracks, sampled and pasted, nearly like a dare. Co-produced with Tim Palmer, as Shaken n’ Stirred had been, it was Plant’s bid to be more than a nostalgia act.

Another thing that stood out was that the songs sounded more fully formed. We can take as an opposing measurement the song “In The Mood” from The Principle of Moments (1983). The first phrase of the song is “I’m in the mood for a melody, I’m in the mood for a melody, I’m in the mood,” repeated three times. Subsequent verses adhere to this same mantra-like repetition. Further in Plant’s pre-Zen catalog, he’s not writing lyrics to necessarily tell stories or make statements. He’s pinning down the rhythm.

But Now and Zen is chasing after far less cryptic prey, and overall the transformation works. The surging, stuttering “Helen of Troy” has a commanding hook for a chorus. “Heaven Knows” and “Dance On My Own” are large-scale pop tunes. “Ship of Fools” is one of the loveliest, most thoughtful ballads he’s put his voice to. Thanks to this approach, the album did very well, going into Top Ten slots in the U.S., U.K., and Canada. “Tall Cool One,” “Heaven Knows,” “Ship of Fools,” and “Dance On My Own” all did just fine on the Rock charts. The critics – past and present – have been favorable to the record.

In fact, it seems the one person who is less forgiving of it is the guy that made it: Robert Plant. He noted in an interview with Uncut magazine in 2005 that “by the time Now and Zen came out in ’88, it looked like I was big again. It was a Top 10 album on both sides of the Atlantic. But if I listen to it now, I can hear that a lot of the songs got lost in the technology of the time.” Fair point, and hardly unique to him. Digital recording was taking the air out of recordings, giving a polished steel sound to them which, for better or worse, immediately identifies the late Eighties output as just that. Sampling keyboards were easy to find and hard to refuse. Guitars were being manipulated to support synths, and not the reverse.

Still, those critics weren’t entirely wrong, and neither were the people who gravitated to the album. It was something very new for Plant. The album was designed to move you, but not really rock you. In many spots, the proverbial tongue was all the way in the cheek, exhibiting a knowing kitsch that piloted the Honeydrippers E.P. Plant made with Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck, and Paul Shaffer. Now and Zen provided a liberation from the icon status that Led Zeppelin bestowed upon him, and in many ways hindered those first solo efforts. “Pop star” was an identity he could assume. It was as much an alter ego as the members of The Traveling Wilburys forged at roughly the same time, forsaking the shackles of being famous in deference to having a good time.

While one can’t say that this album has aged seamlessly – it is a product of its day – it still is having itself a good time.