The 1980s were good for prog rock, provided prog rock was willing to bend a little. Yes would have its biggest hit in 1983. Rush would learn to stop worrying and love the synth. Genesis would ascend from album-side epic songs to the heights of the pop charts. Former Genesis vocalist Peter Gabriel would fold world music, new wave, and expressions of anxiety into his own chart-topping creations.

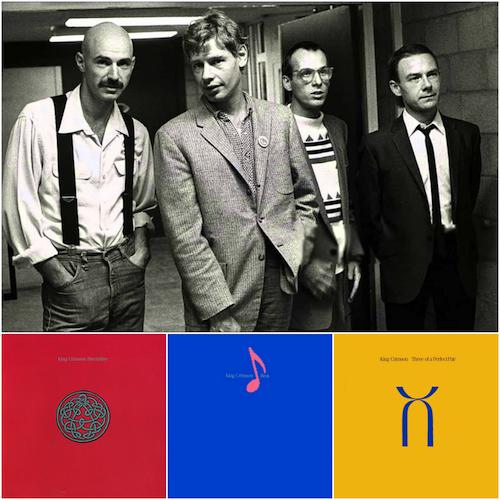

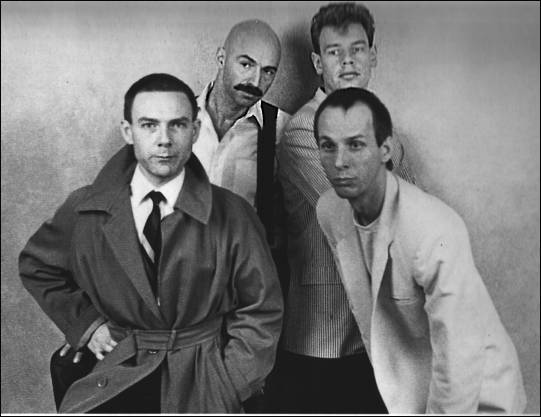

In the very early Eighties, King Crimson founder Robert Fripp reconfigured the venerable band for the umpteenth time, bringing in bass powerhouse Tony Levin and guitarist/vocalist Adrian Belew to join him and previous lineup survivor Bill Bruford.

The resulting Discipline, the first of what would be Crimson’s three icons trilogy (also featuring 1982’s Beat and 1984’s Three of a Perfect Pair), caused some confusion for longtime fans. To this day, with the invention of online social media, one can still dig into how shocked people remain by this lineup.

Belew is something wholly unique to the group at that moment: an anachronistic guitarist with a deep pop music sensibility. Within the context of KC, you’d be hard-pressed to say Fripp is pop orientated. KC started out in the late 1960s as an orchestral-leaning, acid-jazz-fusion group with sinister overtones (thanks to lyricist Pete Sinfield). It turned more proto-metal with vocalist/bassist John Wetton in the mix in the ’70s. The Boz Burrell era is short, and not to knock on his contributions, specifically his bass and vocal double-duty on Islands, but the most salient point that unfairly emerges above the music is that, after Crimson, he helped found Bad Company. (This is a trend in and of itself. Previous and future Crimson alums would include Foreigner’s Ian MacDonald, Wetton as bassist/vocalist for Asia, and Mr. Mister drummer Pat Mastelotto.)

You can hear the tension Belew brings to Discipline. He’s all over side one with the new wave-boho “Elephant Talk,” a proper rock single with “Frame by Frame,” and “Matte Kudesai,” possibly the loveliest and most uncomplicated track King Crimson has ever spawned.

Side two is more spiky, more demonstrably instigating. The push-pull in “Indiscipline” features low skulking between Levin’s bass and Belew’s cryptic descriptions of a “thing” he is toying with, deciding whether he likes this thing or not, whether it is good or not. He is rather cat-like in his delivery and lyrics, stalking the mysterious something. Then in bridging sections, everything erupts in the super-heavy, metallic sound that began in earnest on Red in the late ’70s. The dynamic shifts are unsettling, and that’s the point. That’s the tension.

This gets amped up with “Thela Hun Ginjeet,” which musically – and from the title – sounds like a raving piece of street festival world music. The name, however, is a nonsense anagram derived from “heat in the jungle.” Between the chant-like phrases, what sounds like impromptu recordings of Belew recounting being mugged in the big city punctuate the track. The overall sound is reminiscent of his work a year prior on Talking Heads’ seminal Remain in Light.

“The Sheltering Sky” and “Discipline” offer elegant instrumental workouts that highlight Fripp in the former and both Fripp and Belew in the latter.

I’m actually surprised by the flack Discipline tends to get, although I shouldn’t be. It is both as difficult as KC albums require, but oddly friendly as those times necessitated. I make no secret that I feel the ’80s prog stuff deserves better treatment, even as hardcore fans cry “sell out” because of tracks like “Misunderstanding,” “No Reply At All,” “Owner of a Lonely Heart,” “Touch and Go,” and I could go on. These bands created music that has not disappeared over time and, occasionally, showed flashes of their creators’ prowess. They did what they had to do for the survival of their organizations. The groups made concessions, but I don’t believe they made mortal errors…far from that.

And in terms of Crimson, I think some of the best songs – not jams or experiments, but actual songs – came during this time period. Plus, the band did something with Discipline that was part and parcel with their respective genre. This was progressive. Of the new wave albums that were percolating during this decade, this one sounds least dated, mainly because Fripp’s keyboard washes gird the songs rather than lead them. While I personally enjoy Rush’s keyboard era, it’s undeniable that a track like “Subdivisions” is led by the keys, not Alex Lifeson’s guitar. Later abstractions in pop would find keys taking both lead and rhythm positions, developing a sound that is frequently mocked for being too ’80s. (I’m hearing Journey’s “Be Good To Yourself” and Survivor’s “High on You” – with those persistent ‘nah-nah-nahnah’ keys patterns – in my head at this moment.)

I don’t know enough about the behind-the-scenes dynamics of band members at this time, but it couldn’t have been too confrontational. Aside from the three icons records, all members returned with 1994’s mini-album VROOM and 1995’s THRAK, adding second bassist Trey Gunn and second drummer Mastelotto. Belew would be involved for several years after that.

Lately, the band is a touring-only entity. Belew has been away from KC since 2003’s The Power To Believe. Former Porcupine Tree- and present Pineapple Thief-drummer Gavin Harrison has manned the kit for a few years. Levin and Mastelotto are still in the mix, as is a longtime “projeKCt” member, Jakko Jakszyk. With The Power To Believe as the last studio statement of record, it is difficult to gauge the progress the band has undertaken.

I think that speaks to how important Belew was and remains to King Crimson, even if he does not return in a future configuration. Do I think Crimson would have soldiered on through the ’80s had Belew never been a part of the mix? Sure. Fripp is legendary for his stubborn determination, and I have no doubt that he would have kept the wheels on the bus throughout, but I don’t think that output would have been as memorable or as effective as what we got. And among all these, it would be the greatest shame had Discipline not emerged as it did.