Imagine an explosion, but subtract away the fire, the light, the smoke, the raw crack of sound. What remains is this inexplicable wave of force and heat. It throws you fifteen feet back onto the ground as the burning monster breath rolls above you. All the most obvious indicators of what you experienced were stripped away, leaving you without forewarning.

Keep this image in your mind. We’ll get back to it.

It is difficult to put into words just how put off people were by the release of Radiohead’s fourth album Kid A in 2000. Even though the band had previously shown a perverse delight in subverting expectations, even though frontman Thom Yorke had expressed boredom from the band’s first major hit, “Creep” from 1993’s Pablo Honey, fans and well-wishers still presumed Jonny Greenwood’s big guitar sound would return from around the corner.

That is what people remember most from 1995’s The Bends, aside from the tenderly twisted “Fake Plastic Trees.” That guitar sound which rips open the title track, sounding more like Queen’s Brian May than an alt-rock/Britpop upstart, became an emblem versus an affectation.

1997’s OK Computer created confusion for listeners who thought they had the band pegged. This album was a concept album, a progressive rock examination of the alienating effects of modernity, complete with mellotron keyboards. Greenwood cited Genesis as an influence, particularly on “Paranoid Android.” There were moments that connected the Radiohead of old to this newer effort, but it was evident that the band was trying to go to newer, uncomfortable places. They were rewarded with critical accolades and, generally, fan acclaim. There were still the holdouts that were banking on another Pablo Honey, but those hopes were becoming increasingly unfounded.

By 2000, such a regression would be impossible. Kid A‘s dominant sound is electronic, but not the glassy, shimmering, chrome and neon frequently attributed to “electronic” music. This was electronic with brain issues. It was messy. It skittered when it should have glowed. It chased after thoughts and regularly missed them, rather than falling into sheets of blissed-out humming.

In some ways, it was a homage to the form’s earliest days with Delia Derbyshire in the BBC Radiophonic Workshop during the 1960s, literally making loops of magnetic tape, splicing them together, and running them through tape machines in circuits of five or more. Derbyshire made her sounds from machine feedback, sine waves, and found sounds. It’s this dry, addled, and stuttering sound that Yorke and producer Nigel Godrich latched onto, either specifically or through hazy recollection.

As such, Kid A was polarizing. It was the final nail in the coffin of Radiohead’s big stadium sound. Some people appreciated this thoughtful but baffling metamorphosis. Some sneered and thought it to be pretentious. Still others appreciated it for the pretension. Charges of attempting to be a “cool kid poseur” were leveled against those who vouched for the record. In fact, some of them were.

That album’s followup, Amnesiac (2001), did little to change the internecine mood. The majority of the record was recorded at the same time as Kid A and shares a composition between them – “Morning Bell,” albeit in distinctly differing flavors – and is often viewed as a “part two” of a very long concept piece. That is, those who appreciate Amnesiac feel that way. Those who don’t regard the record as a dumping ground for the cuts that weren’t edgy enough to get onto Kid A.

Like or hate Radiohead, sniff at them for being too artsy-fartsy, but this notion that Amnesiac is a meal made of leftovers ought to be rebuffed. Or, maybe credit is due for just how far they took artsy-fartsy. From the outside, the album’s key track, “Pyramid Song,” is everything everyone said was wrong with the band. It is a moody ballad set to orchestral strings, with a weird time signature that seems to be a failure of music theory more than anything else. Yorke’s voice isn’t falling where it should. Neither are the piano lines. There’s no percussion. The tune is undeniably pretty, but nearly incoherent. It is reaching very far, and from the first minute or so, it sounds like it is hopelessly missing.

That’s the sound of a million fingers advancing the CD to the next track to try to find a guitar.

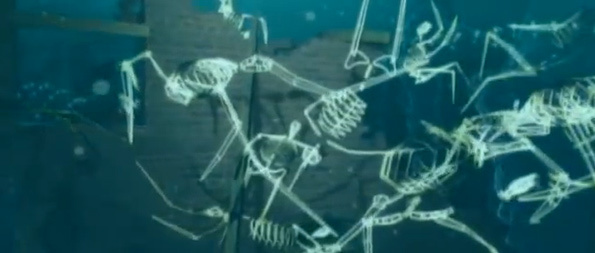

What the band seemingly wanted from the audience was nothing more than patience. For those who actually chose to hang in, believing that this song had to go somewhere, it did. First they had to ride out the blast of air pushing them back, the heat moving above them. They had to handle the explosion without the light, the smoke, clearly-defined crash of oxygen ignition. The “explosion” comes into perspective midway through.

The mind, having been trained for over a century to expect a 4/4 time signature from music, will insert the understanding of that signature when it is not immediately present. That’s the magic ingredient the group is counting on. At that midpoint, Phillip Selway’s drums roll in with a jazz-inflected 3/4 shuffle, and all the parts that seemed off-kilter and purposefully screwed up fall into place. It turns out that “Pyramid Song” is one of the band’s most straightforward, unfussed compositions, but the listener’s expectations inject complication where there is none. Now able to see the fire and the smoke, the person standing in front of the explosion is able to recognize it in its simplicity.

I happen to feel that “Pyramid Song” is one of the band’s most gorgeous tunes, made better when everything gels together. It is not a universal sentiment. I had a heated conversation with a “former Radiohead fan” who asserted that music should never be a trustfall. It should always be ready-to-consume, premixed for your consumption either in the foreground or in the background, and that should be your choice alone. You shouldn’t have to work that hard to be entertained. This person had a point, much as I did not want to admit it, but there can be both in one’s cultural diet.

These conversations break down after some time elapses. One person complained that they wished Radiohead would stop being so uppity and make the music that listener wanted from them, citing that it’s not so bad being Blur or Oasis, is it? (I was prepared to defend Blur as being more dimensional than was given credit, but seeing how I wasn’t sticking the landing with my first offensive and there are only 24 hours in a day, I lost the desire to open a second front.) The point is: asking that from Radiohead would make them an entirely different band, so go listen to that different band that scratches that itch.

This would not be the last time the band experimented with orchestral flourishes (2009’s “Harry Patch (In Memory Of)”) or with confusing construction (2016’s “Spectre,” originally intended for the James Bond movie of the same name). The former is beautiful but overwhelming. It is not a proper song for people with emotional issues or someone who copes with depression (not kidding). It is glorious but incredibly dark at the same time, as befits a tribute to the last surviving British soldier from World War I. The latter, to me, made itself a poor candidate for a Bond theme song. It’s a remit that demands certain well-defined parameters, and in this case, the off-time rhythm trick doesn’t congeal in a satisfying way. In this, you really do have to work hard to make everything stick, and that’s way too much energy to commit to a volatile, pulpy spy thriller.

Amnesiac‘s “Pyramid Song” was the right song for the time with the right intentions in play. For this, the track was singled out one of the best of the decade by Rolling Stone, the New Music Express and Pitchfork. It does expect effort on your part, but it rewards you for the equity you provide, and even now has the ability to throw you deep into your chair with its unseen explosive power.