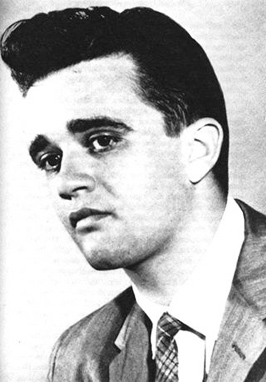

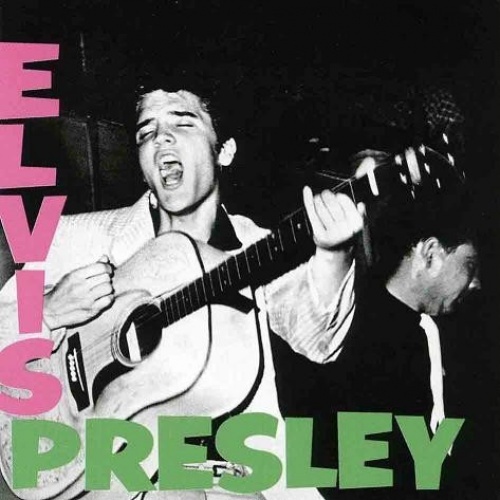

The origin for this series began with a provocative question. On social media, MusicTAP writer Dan MacIntosh disputed an article that asserted that Elvis Presley’s legacy should be reexamined for the crime of cultural appropriation. Fellow MusicTAP writer Robert Ross agreed with Dan, suggesting this level of backward re-litigation has gotten out of control, and in this case is false entirely.

The underlying truth is that, no, you cannot honestly say Elvis stole rock and roll from rhythm and blues. It was clear that musicians like Presley, Carl Perkins, and Jerry Lee Lewis loved rhythm and blues and wanted to be a part of it, not extract it for the “safe consumption” of white people. In fact, it was their love of the music that caused them to be so dangerous.

If, on the other hand, they were only trying to whitewash the music, no one would have been as outraged by them as they were. Presley and the rest of the Sun Records cohort would have been seen with the audible eyeroll that accompanies folks like Pat Boone, with his milquetoast rendition of Little Richard’s “Tutti Frutti.” Here’s where you might be able to make the previously mentioned claim.

As far along as the 1980s, there was still plenty of worry over the pernicious effect of rock on the young. Were it not so, pop culture benchmarks like the movie Footloose would have been meaningless. In that movie, Kevin Bacon’s character moves to a sheltered, rural part of America and immediately scandalizes the populace with his attraction to music, to dancing, and to the preacher’s daughter. But the preacher, played by John Lithgow, knows the score. Rock and roll leads to dancing, dancing leads to sex, and sex leads to…

Such an overheated puritanical mindset seems baffling in 2019, but it still had a foothold in the ’80s, and in the 1950s was on par with the gospels themselves. The term “rock and roll” is itself a euphemism for sex, not dancing. Add in the baked-in racism of it all – that this music was now infiltrating the clean and holy sects of white America and its children – and it’s no wonder that disc jockeys like Murray The K and Wolfman Jack were loved and loathed in equal measure.

What does any of this have to do with the 45?

Imagine post-World War II as boatloads of soldiers arrive back home to America. They’re grateful to be alive, they’re wound up tight because of what we would later call Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, and they were horny. These three factors led to an astonishing post-war birth rate, giving rise to the generation of so-called Baby Boomers. They would be the first youth generation to have real power in the economy, thanks to strong financial benefits when the war effort switched over to consumer products. Because of their numbers, and because they had some money in their pockets, the kids presented a valuable target market.

All The Factors Align – Also post-World War II came the rise of plastics. This is significant because plastics offered more durable products at a cheaper price. Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) is the world’s third-most widely produced synthetic plastic polymer and is the product that constitutes records. (Polyethylene would be used later on for the production of 45 RPM singles.)

Before this, people had shellac records. You have, no doubt, seen these or at least seen pictures of the old 78 RPM records. They were 10″ discs that had the misfortune of being both relatively heavy and markedly brittle. If you dropped one, it broke, guaranteed. Therefore, the purchase of such records was an investment, and care was taken to protect them. And because mom and dad had the money, not the kids, it was mom and dad’s choice as to what the chosen recorded content would be.

There were jukeboxes that played 10″ records, but they were built like tanks, all the better to protect the records inside. The establishment that bought such jukeboxes weren’t likely to want accidents to happen.

This all changed with the youth movement. The youngsters had cash. Records were cheaper and could be bought in more places, thanks to the more-favorable cost-profit ratio. They no longer had to ask mom and dad if they could see it their way to maybe buy something from the pop music list.

Not every region had radio that played rock and roll. There were still plenty of radio stations that held the patrician view that anything harder than a hoedown incited the libido and summoned Beelzebub himself. Yet rock and roll still managed to invade the heartland, in many cases because of the newer versions of jukeboxes. Now, if the kids at the ice cream shop wanted to get up and dance and get rowdy, the records inside probably would not get damaged. If they did, they would be cheaper to replace.

Something else that strengthened at this time was socialization. Cliques formed between teens who liked specific singers. They traded records between each other. Eventually, those radio holdouts had to acquiesce to the want of the listeners and the evident money the station directors were leaving on the table. Again, because 45s were cheaper to produce, more records could be pumped out to markets, and connections were emboldened between radio and the labels, occasionally damaging both because of pay-to-play scandals (more on that in another column).

In essence, thanks to the confluence of factors – a large youth population with buying power; a cheaper, more durable product; a desire to be sociable, to build one’s own fan network, and to share music – the 45 RPM record became the de facto king of the medium. There were no tapes, obviously no digital files, and the era of the album would not dominate until the 1960s. Radio may play the song you want to hear, but sporadically. In the era of the superstar D.J., you were kind of at his mercy. So, if you liked the song, you’d buy the record.

The question then is whether the older establishment was as worried about stars like Elvis the Pelvis infiltrating “black peoples’ music” to their little angels as everyone commonly believes. In part, yes. In equal measure, these adults were fighting to retain the control they once had over the family unit and the social order. The man made the money and, therefore, ruled over. The wife raised the kids, cooked the food, and maintained the house. The kids went to school and did chores because they had to. Previously, they couldn’t do otherwise because they couldn’t afford to. Rock and roll wasn’t the cause of rebellion. It was the free flow of pocket change.

But now they were making independent choices, trading the commodities between themselves in proto-unions of fandom. They were choosing the music of individuals who took rhythm and blues to heart, not rejecting it as a feared deviation from the previously considered “propriety.” They were making these musicians celebrities, making them stars, and making them rich.

It is impossible to say that, had the fragile, doted-on 78 RPM shellac stayed the dominant music ownership format, Elvis Presley would not have had some influence on the culture. There’s every reason to believe that sharing cultural touchpoints, be they musical, visual, or conceptual is an act that cannot be contained. Like Tommy Dorsey, Glenn Miller, and George Gershwin extracted elements of jazz (another scandalous music form) and dropped them into Big Band and Swing, someone was bound to extract the flavor of rhythm and blues and use it the way Elvis did. But thanks to the 45, it happened faster and in a more complete way.

The era of the 45 single was underway. Next time: when 45 singles made albums, and when albums fought back.