1980 was a pivotal year for rock music. Many acts who cut their teeth and had a good amount of success from the late ‘60s through most of the ‘70s were faced with a changing musical landscape. Punk, disco, and new wave had an effect of segmenting the market for R&B-based music into niches that were getting more challenging to fit into. Some bands were able to adapt to these changes — like The Moody Blues. Coming off a less-than-stellar album in 1978, a split with keyboardist Michael Pinder, producer Tony Clarke, and a lawsuit to boot, the band — while briefly stymied by litigation initiated by Pinder — was bursting with song ideas. Indeed, by the time The Moody Blues entered their custom UK studio to record what would become Long Distance Voyager, they had a new producer (Pip Williams) and a keyboard player (Patrick Moraz) who would help create one of the most successful records of their career. As guitarist and songwriter Justin Hayward told Louder in 2014, Pip Williams was able to update the band’s sound “without changing us.” That’s not an easy thing to do when a group like The Moody Blues really defined their sound over the course of several records between 1967-1972. After taking a break from touring to work on solo albums, the band regrouped in 1977 only to find that the dynamics had changed. Without getting into the weeds about what led to a split with Pinder and Clarke, it suffices to say that by 1980 The Moody Blues faced the new decade with an opportunity to go in a new direction — and one that ultimately paid off.

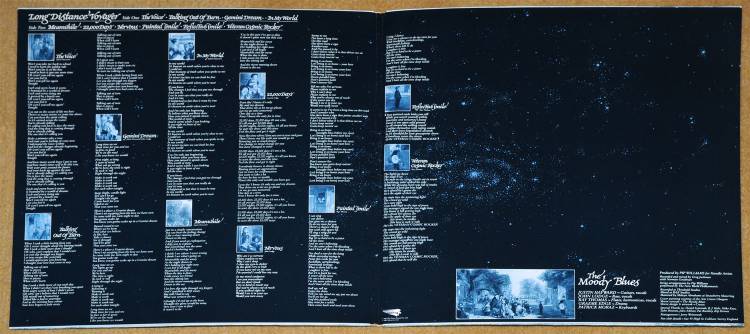

The opening track on Long Distance Voyager, “The Voice,” signals this is a new kind of Moody Blues. The dramatically layered keyboard work that Moraz lays down has a very contemporary sound, and one that shows a revitalized band has come back on the scene in a powerful way. When Hayward sings, “Won’t you take me back to school/I need to learn to learn The Golden Rule” it could be an allusion to the band’s difficulties with Pinder and Clarke. But, lyrically, the song also speaks of listening to that inner voice (or spirit) calling out to face the music. It’s a nice clarion call to rise above the petty (and not so petty) fights in order to follow one’s dreams. “The Voice” is not without its dark side, but overall it’s a wonderful first track that starts the album off in a forceful way.

“Talking Out Of Turn” isn’t quite the high-minded song as “The Voice,” but it does find bassist John Lodge writing an effective mid-tempo number about conflict and hurt in a relationship. In “Gemini Dream” Moraz again supplies the band with a lot of sweetening from this arsenal of synths that takes a kind of four on the floor rocker and elevates it into something ELO might have done. But Moraz isn’t the only one adding to the strength of the tune. Hayward, Lodge, and Edge play wonderfully, but there’s no doubt the coloring Moraz adds keeps the song from slipping into the past in terms of style. Sure, “Gemini Dream” sounds more than a bit dated decades later, but it’s still an outstanding composition that shows the Moodies in top form.

“In My World” is clearly a Classic Coke Moodies sound — mostly because it’s a straight- from-the-heart love song that Justin Hayward excels in crafting. The lyrics are earnest, the guitar work is very tasteful, and the background vocals featuring Ray Thomas have a kind of atmospheric effect that doesn’t overpower the intimacy of the song. I give both producer Pip Williams and recording engineer Greg Jackman a lot of credit for making “In My World” soar with their production work. It’s not an easy thing to balance the number of musical elements that went into this tune, but Williams and Jackman had both an ear and a vision for how it should sound.

“Meanwhile,” suffers from its placement on the record. It follows “In My World” and has a similar feel to it — mostly because it’s another Justin Hayward tune. Not that it’s a bad song, it’s just that it would have been nice to have a different song in its place to offer listeners something more stylistically diverse — which is what happens with “22,000 Days.” Drummer and founding member of the band, Graeme Edge, wrote this song with the enigmatic title. If you do the math, 22,000 days is 60 years, so one wonders if Edge is trying to say that it’s unlikely that he’ll be in a rock band after the age of 60. Well, like The Who hoping to die before they get old, Edge was well past his expiration date in 2020 — and touring with his band. Nevertheless, “22,000 Days” is one of the more adventurous songs on the album, and one that really harkens back to the progressive rock period of the band. Not so on “Nervous,” which has John Lodge on lead vocals. Like Hayward, Lodge often writes songs that focus on love and relationships, and so it goes with “Nervous.” The song starts with some nice guitar work from Hayward, a tasteful use of Ray Thomas’s flute playing, and an intimacy to the vocals. However, where it kicks into high gear is the pre-chorus that leads to a nice release. Later in the song, Moraz’s keyboard — along with a string section — adds some sonic filler in a way that takes it well beyond its acoustic guitar beginnings.

The album hits the Long Distance Voyager theme in the last three songs — all written by Ray Thomas. “Painted Smile” is from the point of view of a clown, and while it’s a kind of well-worn trope of “laughing on the outside/crying on the inside” Thomas’s hippy-like earnestness is a welcome counterpoint to the direction of the album. And what Moody Blues record would be complete without some spoken-word poetry? Well, we get that in “Reflective Smile” — a short interlude before the album closer. When Thomas intones ominously to “be thankful for your grease paint clown” he seems to be saying that, like a clown, being in a rock back has similar pitfalls as a jester. Lodge noted something similar about “Gemini Dream” where performers like him “become two different people when you’re in a high-profile band. There’s the person onstage, and then there’s the private version of you.” Thomas picks up on that theme and makes it clear that a clown, jester, or artist’s life can be a lonely one (If loneliness wears the crown/Of the veteran cosmic rocker) as he transitions from jester to rocker by mumbling slightly off mic, “I’ll have a scotch and Coke please, Mother.” With that,“Veteran Cosmic Rocker” starts in a grand fashion. The song is reminiscent of “I’m Just a Singer (In a Rock-n-Roll Band), in that it’s a pounding rocker that begins with some thunderous drumming from Edge. Like the other tunes Thomas wrote for the album, “Veteran Cosmic Rocker” is about an aging performer (this time, though, a rock star) who is feeling that time is running out on him as he walks out onto the stage with “his arms held high in a sign of peace.” It’s clear the image evoked by that lyric finds Thomas questioning his relevance in 1980-81. Musically, however, the band constructed a response to Thomas’s question — and it comes in the breakdown and bridge section. The Bo Diddley beat that anchors this part of the song seems to suggest that from bluesy harmonica to Middle Eastern rhythms, an R&B beat endures through the ages. If there were a song that encapsulates the career of the band up to that point, it’s “Veteran Cosmic Rocker.” The Moody Blues pack so much into the three minutes and nineteen seconds of this tune, but they do so in a way that’s not heavy-handed or belabors the main point. “Veteran Cosmic Rocker” also represents the last gasp of the spirit of the 1960s and early ‘70s for the Moodies. Sure, they would go on to do well in the ‘80s and part of the ‘90s as they became more of an Adult Contemporary band. However, like the fading sitar heard on the final moments of Long Distance Voyager, it’s clear the spirit of the 1960s did indeed die for The Moody Blues after 1981.