Arriving in 1983, the band The Flaming Lips was already an anachronism, unapologetically psychedelic, and prone to agitating against the mainstream even as it longingly gave it some side-eye. That kept the band on the fringes, but close enough so that they could actually have a bit of success, particularly with the track “She Don’t Use Jelly,” from 1993’s Transmissions From The Satellite Heart. Their big breakthrough, 1999’s The Soft Bulletin, was their most subversive move of all. It was song-driven, focused, and full of the possibilities that pop-structure could afford. The band was like the teenager finally allowed the keys to the family car, at once respectful and fearing the responsibility and, at the same time, possessed by what kind of righteous damage they could do.

2002 brought even greater acclaim with Yoshimi Battles The Pink Robots and a bona fide hit with “Do You Realize??” (and some foldin’ money with the song being licensed for TV ads). Perhaps as a reaction to this acceptance, 2006’s At War With The Mystics introduced a level of harshness to the formula, ostensibly to regain their freakwave status and dispel notions of having sold out. Consistently since then, their records were noisier, more abstract, and harder for the average bloke to accept. Their core fandom was, I must assume, pleased.

But for the others, the band regaining the throne of psyche-rock provocateurs stung a bit because, even if they were rebelling against “normal” pop songcraft, they had the unfortunate curse from it that their neo-psych peers might not have: they were excellent at it.

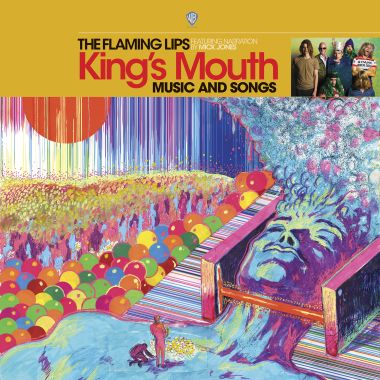

For Record Store Day 2019, the band dropped a new album in honor of the 20th anniversary of The Soft Bulletin that, while not directly an homage to it, certainly exemplifies the ethos of it. Warner Records is now releasing King’s Mouth: Music and Songs wide, and it comes across as bittersweet. The 12-track album features narration from none other than The Clash’s Mick Jones, telling the tale of a giant, a child of the universe, that makes the ultimate sacrifice to save the city, and yet the people indebted to him cannot let him go.

The record regains that ability to focus on structure – a word I’m afraid I’ll be using a lot going forward – and this produces “song” songs like “The Sparrow” and “How Many Times.” Jones’ narration occasionally drives a track or two, but overall, Lips leaders Wayne Coyne and Steven Drozd (in reduced collaboration with longtime compatriot Dave Fridmann as an “additional” producer) are aiming for that sweet spot they found on Bulletin and Yoshimi, and it works. King’s Mouth is still trippy, still unmistakably Flaming Lips, but is more accessible than they’ve been in years.

“Accessible” is a loaded term. There’s nary a shout-out to indigo vagina-fart rainbows to be found over scratchy, lo-fi electronics here. Yet, fully half of the record deals with the birth and life of this universal king. Midway through, he dies to save his citizens. Still, they cannot bear to be without him, so they behead him, dip his head in molten steel, and take turns climbing in his mouth to see the stars contained therein. It is bizarre, and yet carried out with a restraint that runs counter to the fantastical premise.

I think there’s bound to be many who have problems with King’s Mouth, and not for the narrative weirdness or the fascination with death and its implications. The Flaming Lips have always had such an inclination. In fact, The Soft Bulletin was not the original title for that album and was, instead, The Soft Bullet In, according to Coyne’s witness. (It’s difficult to say with certainty whether this is true or he was merely yanking an interviewer around, which is something he liked to do from time to time.) The problems may arise from this record being amiably pleasing and ultimately pleasing few, as it is not the warped burnouts that Embryonic or The Terror were, but it is also not a collection of self-contained tunes invented by committed weirdos. Yes, the songs are structured, but this is a concept record that heavily leans on its trappings to hold it all together. “How Many Times” is being sold as the record’s first single, and it can stand apart from the collection well enough, but it loses something without its framework (much like a head without a body).

The other side of this is there was a transgressive perversity to how The Lips once embraced their mainstream side which is unattainable now. The pop-rock they seek to emulate again is not mainstream anymore, and they’re not the younger pranksters they used to be, tweaking the stiffs. They’re not spinning yarns about being old people, mind you, but their flirtations surrounding mortality hit closer, and even in the relative madness of a song cycle about giant kings and the idols created in their absence, they are hinting at being too much in love with a past that the populace can’t seem to let it go, and that idolatry supersedes the thing it represented. Essentially, The Soft Bulletin and Yoshimi are dead, but the public has dipped these things in metal to act as the end-all-be-all that inhibits growth, and also forms unrealistic plateaus that can’t be climbed again.

It’s that aspect that is fascinating but, at the same time, kind of dispiriting. The band, no longer a teenager with the keys, is fully aware of the damage they could do now, and that understanding has to play a role in what comes after, either consciously or subconsciously. The band knows that this record, while a tribute to that time period and what was created then, will be undercut by legacy and won’t have the freedom to live on its own. As good as it may be (and it is very entertaining), it has to compete with the “giant steel head” of the past.

My advice is to enjoy it for what it is, and attempt to forget about what it is not. There’s a lot to like about King’s Mouth if you are ready to accept it at face value.