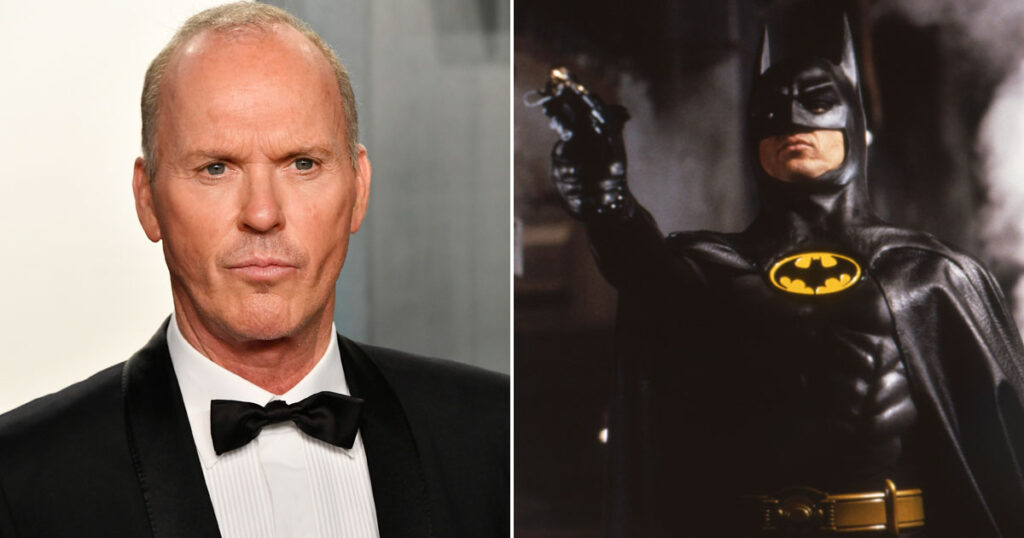

Alfred Molina is returning as iconic supervillain Doctor Octopus, but it’s in the Tom Holland version of Spider-Man, not the Tobey Maguire version. Ezra Miller’s version of The Flash, a part of the Ben Affleck-Batman Justice League, will be speeding headlong into Michael Keaton, returning as…Batman. There are other crazy crossovers being mentioned, too.

What gives?

As anyone who has a glancing understanding of comic books, especially those from the ’70s and ’80s, will tell you, this is not all that weird. Creative teams on a comic book would regularly make far-reaching changes to a storyline. The teams would be replaced with another writer/artist duo who would do the same. Over time, continuity would go haywire and one of two remedies would occur – either the incongruities would be explained away by saying the events that occurred were on alternate earths, or there would be a major character crossover event wherein undesirable duplicates were changed, rendered harmless, or killed off.

But this was never a problem with the movies before. You had a film arc, typically two or three movies long, then having fulfilled the contract, the star would move on to new projects. Production companies seeking to retain control of the intellectual property in their licensing deal would greenlight another series as soon as possible. Maybe the new series would connect in some way with the old, but very often, all involved started over at Square One. This is why Sony jumped into making the Andrew Garfield Spider-Man movies shortly after Maguire’s run came to an end.

There were no serious consequences in doing so before. The movies were shown, the DVDs were made, and the rights to broadcast lapsed to cable TV and into syndication. The studios did not care that the latest had no connection to the previous. In fact, they’d prefer you forgot the previous ever existed. There were no profits to be had from them anymore.

That was then. To explain now, we have to think about a very small public library. It gets subsidized by the township, but only if it keeps gaining users, so those library cards need to be flying out the door on a regular basis. To accomplish this, they need to be very strategic about what gets on those very short bookshelves. Obviously, you need to make room for the latest and greatest. One Mr. Stephen Edwin King has written 63 freaking novels, issued 11 short story collections, and more. You can’t keep them all. Which ones go? Do you cut any of the Dark Tower books? That makes no sense. What about so many books that seem to have no connection to each other? Okay, that might work, but King’s people want his books in the library because people tend to buy the books after they’ve read them for free. There is a financial interest in keeping them there.

So what would happen if Stephen King wrote a massive novel that tied together his entire 50+ career, made the Castle Rock narrative a driving point of every single thing he ever put to paper, and this little library had every last one of these books on tap? Would you want to be a member of that library? Would you get that library card today?

Movies are no longer just movies, they are “content.” They no longer end up on digital discs that act as IP cul de sacs. But at the same time, the Tom Holland version of Spider-Man is a cash cow for both Marvel and Sony. There’s no great reason to go back and watch the Tobey Maguire or Andrew Garfield Spider-Men. While streaming services have massive data storage situations that contain multitudes of “content,” they are not infinite, and things need to be cut. New subscribers demand the latest and greatest but they also want access to continuity. Here lies the problem.

The solution: the multiverse. You can retcon a continuity into preexisting releases, giving them a contrived freshness, and ensure that every bit encoded on that digital storage system is driving new subscriptions. It doesn’t hurt that there’s a fair bit of wish-fulfillment involved. Who doesn’t want to see Keaton as Batman again? But now, the two Keaton/Batman movies have purpose beyond nostalgia, and that’s positive content for HBO Max. (I suspect that’s also why James Gunn’s The Suicide Squad, despite all the cagey denials, really is a sequel to David Ayer’s Suicide Squad, and both fuel the upcoming Gunn TV show The Peacemaker with John Cena reprising his role from the film.)

What does that mean for future movies, television, and what-all? It means a landscape where everything is canon. It’s a new age of interconnectedness because they have to be. To be standalone is to arrive immediately dated. If you were burned out on the endless loop of prequels, sequels, reboots, and “reimaginings,” just wait. In an asset-management world, even the old stuff has to be made new somehow. It’s their multiverse, we’re just living in it.