Lost and shut out from all the love for the vinyl revival has been the lowly 45 RPM record.

It’s not without good reason why this format, which would seem the perfect venue for the modern singles-only music model, hasn’t reconnected, both from a practical and a philosophical standpoint. From the practical side, there are three drivers that supported the 45, even into the late 1980s that no longer exist.

First, 45s used to be cheaper to produce than 12″ vinyl records. When record labels had consistent manufacturing plants at hand, a spindle of 45s could be turned out quickly. That’s not the case anymore, with specialty record plants dominating the landscape and labels competing to use their services.

Plus, a large majority of 45s cannot be called “vinyl” at all, but were made from polystyrene. You can tell the difference almost immediately as vinyl-pressed 45s have a smoothness to them overall and the paper labels are heat-merged to the plastic compound much as a 33 RPM record’s would be. WEA (Warner, Elektra, Asylum) were known to go the traditional route with PVC (polyvinyl chloride). Mercury, RCA, Arista, and others did not. You could see the records were flatter, brittle, and the labels were more like pasted-on stickers. These records wore down hard and fast, as consumers were known to use them in harsh ways (the penny taped onto the tonearm to keep the needle from skipping, for example).

Second, 45s were a perfect medium for jukeboxes. The discs were small, could be stored in series, and again, were cheap enough to change out on a regular basis to accommodate the influx of the latest hits. Mix CDs and, eventually, digital files all but eradicated the traditional jukebox format.

Third, 45s were the staple for labels to break new artists with radio stations. You have, no doubt, seen the “white label” versions of 45s that also state that the records were “for demonstration purposes.” They’d frequently have the same song on both sides, occasionally backing a stereo version with a monophonic version.

When radio stations had more control over what got played, such demo discs were invaluable and could help a program director discover new talent. Today, setting aside the corporate conglomerates that have cornered the radio market and surgically winnow the playlist down to only the top 30 songs in constant rotation, independent stations are just as challenged. Rock radio has devolved into classic rock radio, endlessly regurgitating a stream of predictable nostalgia. And if the radio station does engage in regular discovery efforts, it’s done through digital files, not demo 45s. There’s still no guarantee that it will shake the station out of its constant playlists of “Sweet Child O’ Mine,” “Born in the USA,” “I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For,” or “Don’t Stop Believin’.”

I have not, however, come to bury the 45. There are unique attributes to the format that, while not ideal for the audiophile, are at the very least endearing, and at most a treasure trove for fans of specific bands, particularly with bands that emerged from the U.K.

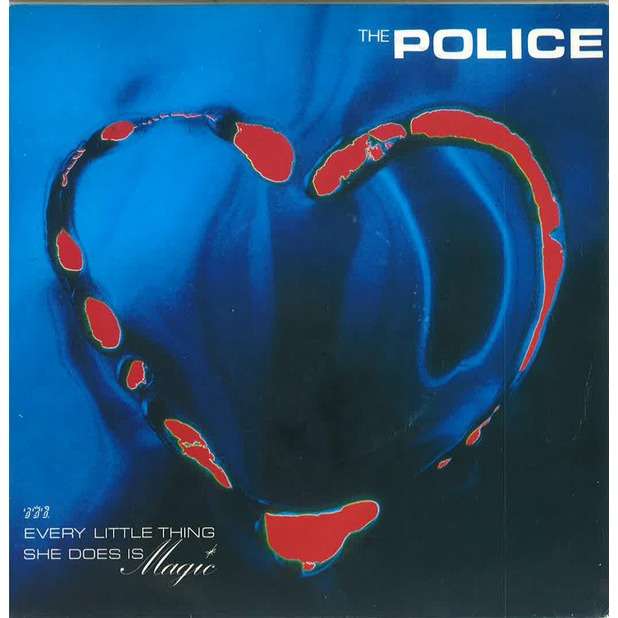

The most obvious plus for the 45 was that it often came with a picture sleeve, and the imagery on such a sleeve was different from those on the full album’s cover. For only a buck or two, you could stare in lovestruck ardor at your favorite star, providing the label was savvy enough to understand this marketing potential.

To give fans a little extra thrill, 45s would occasionally be issued in different colors. Electric Light Orchestra (and label Jet Records) released “Telephone Line” on transparent green and “Sweet Talkin’ Woman” on transparent purple. Grand Funk Railroad put out “We’re An American Band” on vivid yellow. These upped the curio value to collectors but, because the 45s market has not rebounded like the 12″ market has, all these titles are still easily found on Ebay and at flea markets at less than a buck a piece in good condition.

Bands located in the U.K. prioritized the 45 as its own specialty release, and often recorded songs specifically for the b-sides, thus validating the term “the b-side.” The Police were well-known for this, with nearly every one of their hits on the format backed with a song not available on the LP. While technically a double a-side with “Hey Jude,” The Beatles’ rock version of “Revolution” (versus the slower strolling version found on “The White Album”) was only available as a single for years, as was the bizarre “You Know My Name (Look Up The Number).” Many of these tracks were not available in another format until they were consolidated into box sets and on comprehensive CD reissues. And still other tracks have not been commercially issued on any format other than the 45 b-side, meaning that there are full chapters of some artists’ careers still lost to the sidelines.

Throughout 2019, MusicTAP is going to take a deep-dive into the world of the 45 RPM record, determine its many shortcomings, and celebrate its attributes. We’ll have pictures and links to share and, maybe, we’ll encourage you to look into this record type which presently looks to be doomed to the world of the relic. This is not meant as a case for reviving the format, since the deficits which hold it back are as true today as they were when the such singles disappeared from convenience store shelves. This is, instead, an appreciation of what was, and an examination of why it worked as well as it did as a marketing tool for so long. We hope you’ll join us on this tour throughout the new year.